How Somaiya Vidyavihar turned two rural Marathi schools into model institutions

“What you get from society, you must return multifold.” That, in short, was Padmashree Karamshi Jethabai Somaiya’s philosophy, which is entrenched in the values and work of Somaiya Vidyavihar, a trust he established in 1959. Born in the early 1900s to a poor family, he could not study beyond grade VI. In 1939, a poorly educated Somaiya built sugar factories in Sakarwadi and Laxmiwadi in Maharashtra. The sweet success of his factories gave rise to the K. J. Somaiya College of Arts and Sciences in Mumbai and the Somaiya Vidyamandir Schools in Sakarwadi and Laxmiwadi, where most of his employees lived with their families. The Sakarwadi school was built on the banks of the Godavari for children of the Kopargaon taluka, Ahmednagar. Today, poor children from neighbouring villages like Wari, Sade, Bhojade and Dhotre in Kopargaon,n and Nighoj, Shirdi, Rui and Dorhale near Rahata taluka travel to attend classes.

In the rural landscape of Maharashtra, the Vidyamandir schools underwent a transformation 13 years ago when the President of Somaiya Vidyavihar and Chairman of the Godavari Biorefineries Ltd, Samir Somaiya, visited them with his two-year-old daughter. The fateful visit resulted in the establishment of schools that boast of science laboratries, movie halls, libraries, computer laboratries and a music hall today. The village children of Kopargaon and Rahata were no different to him than his daughter. Feeling they deserved the same quality of education as English-medium schools impart, he was renewed with strong determination to turn Jethabai Somaiya’s sweat and blood into model Marathi institutions.

Samir’s belief in developing regional language schools into bastions of knowledge has brought to rural Maharashtra a robotics workshop by K. J. Somaiya College of Engineering and Information Technology; sociology students and professors from S. K. Somaiya Degree College of Arts, Science and Commerce to develop both schools; Cornell University faculty and students to discuss teaching methods and science experiments; and ex-directors of the Nehru Planetarium who conduct star viewing field trips and play space documentaries for students (the schools have their own telescope).

Samir Somaiya feels being born in a taluka is no reason why rural children shouldn’t be exposed to the rich world outside. That commitment to quality education has led to near perfect results at both schools, which perform well not despite being Marathi institutions, but because of it.

Sunita Pare, principal of Somaiya Vidyamandir at Sakarwadi, says teachers need to be more involved in students’ lives than what is generally seen in schools. “We help them when they need support for difficulties they’re facing, and motivate them when they do well in their studies as well.” Challenging impediments rural regional language schools face is only possible if teachers, she says, are always accessible. Parents are counselled on why education is important; they are kept in the loop on their children’s progress; and told what they can do to help enrich their children’s life.

A testament to how access to hygiene can make or break a child’s future in India, Pare says parents are more confident sending children to school when they know it has good toilet facilities, especially if the child is a girl. As Mid-Day Meals are handled by Godavari Refineries, there’s better quality control compared to government schools.

Pare talks about how infrastructure is important to education, whether it’s spacious rooms or ventilation. The walls are decorated with charts and designs by students to give them an ownership of the space. Sports, from football and hockey to rural games, music and dance play an important role in the school. “All the students,” Pare says, “are encouraged to participate and perform well in the inter-school competitions at the taluka-, district- as well as state-level. To give the children greater exposure, we often hold district level championships. This allows our students to meet students from across the state.”

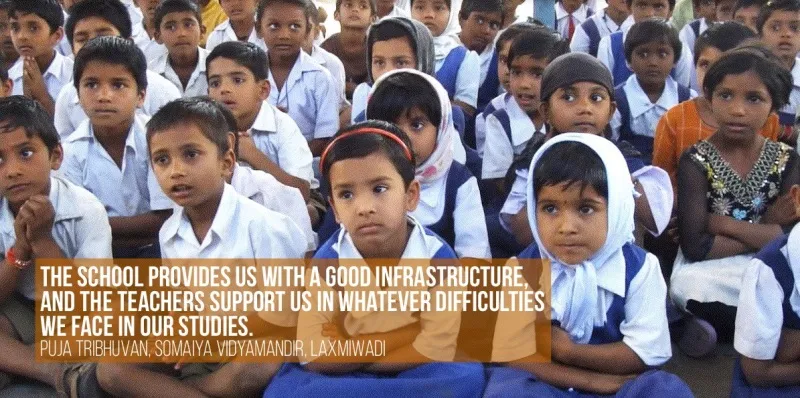

Puja Tribhuvan recently passed her SSC from Somaiya Vidyamandir, Laxmiwadi. From a very poor family, her father works as a wireman and her mother, in a sweet shop. She says, “We live in a rented house.” At Somaiya, Puja says she was only able to improve because of the unfaltering and patient support of her teachers. She especially found Sanskrit and English difficult before her teachers encouraged her. Puja says, “The school provides us with a good infrastructure, and the teachers support us in whatever difficulties we face in our studies.” She likes the visits by international guests and the routine Somaiya Vidyvihar visits from Mumbai.

Puja hopes to become an engineer one day. Ever since her impressive results, she has a renewed confidence, and genuinely believes that her aspirations are not fantasy. She says, “I can now look at the future with great hope and determination.” She adds: “Like our school teachers, other school teachers should be open and involved in the child’s development. They should be available to clear their doubts and difficulties so that students do not hesitate before approaching them.”

Devyani Gagare, from the same school, also has big ambitions. When she was only a child of four, her father abandoned the family. Ever since, she’s lived with her mother, a primary school government teacher. Girls in rural schools have very little exposure to sports, let alone a decent education. But with the backing of her teachers, Devyani is a state-level badmintonplayer, besides already being a district champion in table tennis. Devyani says, “The teachers are highly qualified,” and that the best part about her school is the sports facilities. Lucky enough to be a part of Somaiya Vidyamandir schook, she feels equally confident of her future as her peers.

In Sakarwadi, Tanuja Kale has just passed her SSC. Born to a farmer and housewife, she says she started school facing difficulties in many subjects. But with sustained effort on the school’s part, she was able to top the National Talent Search Examination.

Nevertheless, teachers like Pare have their work cut out for them. “For students with low-income backgrounds, even the basic needs are a challenge to be fulfilled. They do understand the importance of education, but are often not able to give the attention that it needs. For them, just making their daily living takes their time. They are not able to support their child at home for studying.” It’s easy to talk about preserving childhood, but poor students often have no choice but to lend a helping hand to support their families. When putting a meal in on the table becomes a matter of good fortune,, having an extra pair of hands to help is a desperate measure. “So,” Pare says, “we have to be understanding of their conditions, and ensure that the children remain motivated. Thus making education affordable and accessible is very important. Also important is for parents to see that the school is of a good quality, so making the sacrifices needed for the child to study there will be worth the effort.”