Asanas on wheelchair: Guru Syed Pasha takes yoga to the differently abled

More than four decades ago, in the ragi town of Anekal, Syed Salahuddin Pasha was born to a Muslim family which traces its lineage to physicians who worked for the Kings of Mysore. “We come from a family of healers,” he says. So it was only natural that Syed would continue his ancestors’ legacy. His practise of yoga began when he was only a child of six, slim and nimble. Of his religious heritage, he unequivocally states, “I have studied the surah and the shloka. No religion teaches you not to learn good things from others. I feel, personally, it is my moral responsibility to teach yoga, because it is about equality, equity and empowerment.”

Guru Pasha felt if there was a community that desperately needed a union of the soul, mind and body, it was the differently abled one. Over 40 years, he developed a philosophy of yoga to bring persons of disability (POD) back into the world they had been forced out of by a country considered one of the worst places to be disabled.

For Guru Pasha, much like his counterparts, yoga isn’t a fad, but a philosophy of life. A follower of men like Swami Vivekananda and Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, the foundation of his yoga lies in the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, a 400 C.E. compiler of the sutra. When he teaches yoga to the differently abled, Guru Pasha’s ultimate goal is for his students to attain balance in pancha bhoota, the elements that make the Universe. It’s not simply a series of yoga-like exercises, but a mélange of music, dance, chants, postures and spirituality.

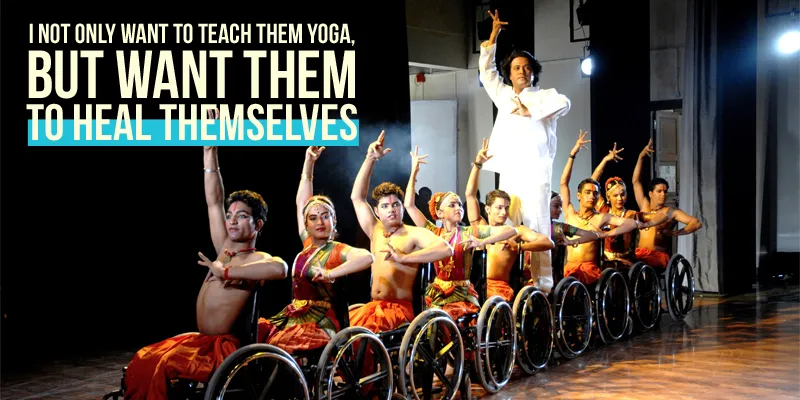

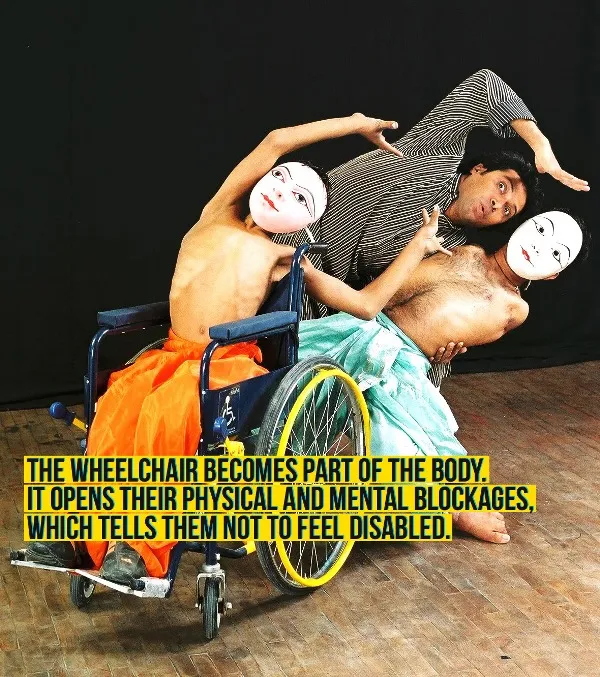

“I not only want to teach them yoga, but want them to heal themselves,” says Guru Pasha, “through karma yoga, dharma yoga and adhyatma yoga.” He also believes that being one with nature is important for many people to start their healing and self-discovery, and eventually break out of their husk. In his earlier days of study, the Guru would perform his padmasana, shavasana and pranayama on water. “The disability that people have may be a birth defect, an accident, disorder or mental disability. Yoga simply brings them confidence; it brings out their outstanding abilities – their inner strength.” For instance, Guru Pasha’s wheelchair-bound students perform shirshasana and mayurasana, two of the most difficult asanas, on wheelchairs, as part of complex dance routines. “The wheelchair becomes part of the body. It opens their physical and mental blockages, which tells them not to feel disabled. It really does transform the way they look at life; it makes them independent.”

At Ability Unlimited Foundation, a charity organisation Guru Pasha founded, yoga is practised as a fusion of dance therapy, music therapy, traditional yoga therapy, group therapy and colour therapy. Dozens of students overcome physical and mental challenges to don prismatic designs and perform yogic dances on stage. “Dance is nothing but yoga. When you practise the most difficult jati, you cannot miss a single tala. So their concentration level increases in yogic dances.”

Running an organisation around yoga has its own difficulty, especially when the students are differently abled. “Each person’s disability is different. I have to do lot of counselling with them, their parents and what background he or she comes from,” says Guru Pasha. For many, it takes years to heal the psychological trauma or depression that comes with disability. On his work with tsunami-affected children with disabilities, he says, “They had totally become lost. I used meditation to calm them, to remove the state of fear in their mind, which was very strong.” It’s a slow and gradual process, which, Guru Pasha believes, is how yoga should be primarily practiced. If you want to live like the tortoise, then you must slow down; but if you become a dog, then your life will be short, too, he says.

As the popularity of yoga increases, so does its transformation into a glamourous commercial product to be sold. If anything, yoga has become an expensive affair, a lucrative business or a gimmick where thousands sit together to perform a few asanas. “I call it scrap,” retorts Guru Pasha. “Yoga has to be learnt from a guru shishya parampara. I don’t want to name gurus, but you can’t just say ‘do this’ and ‘do that’. This applies to able-bodied people, too. How will you know what problem a gentleman has? Yoga has to be one-on-one. I do medical yoga with a friend, and we do it very seriously! When you have hurt your back, how can you do chakras? You have to only do asanas which don’t affect your vertebral column – the home of all the seven chakras – which is the tree of your body.”

For a man who learnt yoga out in the open, barefeet and dressed in cotton, he has strong reservations against those who’ve turned yoga into a fad where you spend thousands of rupees on tights and mats.

For a few weeks leading up to the International Yoga Day, a puerile quarrel had broken between political factions over yoga. Being a Muslim yogic, Guru Pasha says, “I see myself as a symbol of national integration.” For the Guru, the humming of millions circumambulating the Ka’aba, the Vedic chants, the Christian hymns and every spiritual recitation that is repeated over a rosary is a divine vibration with one meaning: unity of the mind, body and soul. His only imperative is to bring that experience to a historically neglected community. He says, “My individual opinion… is that everyone should practice yoga.” Even prayer, after all, is a suryanamaskara.