When a company hits a downturn

Handling a downturn has very little to do with what you do when the downturn starts, but a lot more to do with how you built during the boom. At the start of a downturn, if you’re asking “What do I do now?” It’s probably too late.

We are optimists. As venture capitalists it's in our nature to focus more on the “what if” over the “why not”. This enables us to take risks and dream about the world in a unique way. It helps us relate to entrepreneurs and have the right temperament to start new businesses. Despite our optimism and risk-taking nature, once we invest in a business, we become the pessimists at the table. Having lived through cycles, we have learnt that we have to balance the euphoria of the new with a sense of caution about the realities of the world.

Indian entrepreneurs have had the good fortune of living through a boom cycle for the past 18 months. During this time the average Series B and C financings have gone up by 60% and the average Series D financing has increased 80%. The time between rounds has dropped from 24 months to 15 months and in some cases has been as little as two months! By all standards India has seen unprecedented investment in the enablement of dreamers to build exciting businesses. While this has been a boon to entrepreneurs (and consumers who are living with amazing discounts and deals), the tide is bound to turn. (Indian startups raised $3.5B funding in the first half of 2015)

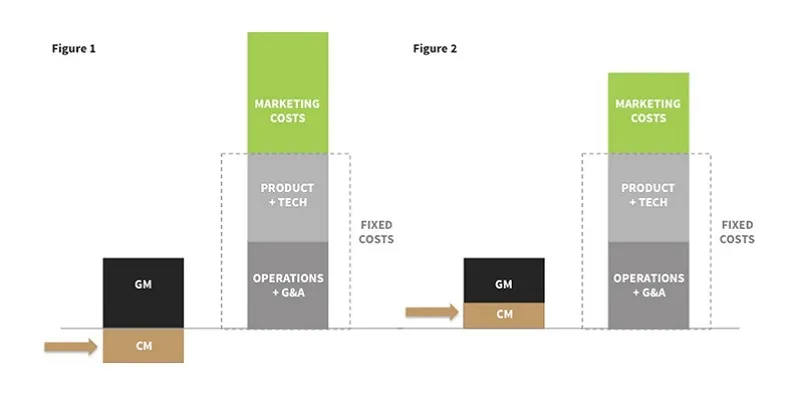

Before we can understand what to do when the tide shifts, it is important to understand where some of the challenges come from. When a company starts, the majority of its costs are fixed – product, technology, operations, and overhead. Once the product is built, the business starts to sell and generate revenues and gross margin. However, at this early phase educating and acquiring new customers is expensive. The cost of customer acquisition (CAC) is high and the therefore the business has to live with a negative contribution margin (CM) and a rapidly growing marketing expense (Figure 1). Entrepreneurs and investors are willing to endure this high CAC/negative contribution margin as they believe that if they keep scaling, building awareness and repeat purchases, the blended CAC across new and returning customers will come down and eventually generate a positive contribution margin. This positive contribution margin will grow with more sales and eventually recover fixed costs and generate a profit (Figure 2).

This approach of endure a high burn as you get to scale and then optimise once you get there has worked in many instances, so the leash that investors are willing to give entrepreneurs to explore this model (and the cash burn they are willing to fund) has gotten longer and longer. During up-markets, companies are encouraged to focus on scale with the promise that the capital required to fund this high CAC/lifetime value approach would be forthcoming.

This works … until it doesn't. When the market corrects, investors change their tone and worry that as capital dries up chasing scale may no longer be viable. This is not to say that investors were wrong with their scale strategy or fickle in their approach, but it is recognition of a new market reality where risk capital to fund burn for scale may no longer be available. Businesses need to adjust. Unit economics come to the forefront and conversations focus on profitability and sustainability as opposed to scale.

Building an organisation that can handle the conflicting demands of scale and unit economics starts with thinking about what costs are absolutely essential. Ensuring that the majority of fixed cost spends goes towards product and engineering, as they are the true value drivers. The bare minimum should be allocated towards overheads. This seems like a simple thing to do, but when a company is scaling rapidly, management often loses track of overheads and “special projects” take on a life of their own. The best time to put in place operational discipline is during an upturn. By being aware of these risks companies can use the good times to not just scale, but also build an organisation that is “fit and healthy” instead of “fat and slow”.

This was a painful lesson that we learned at Cleartrip in 2008. We spent the first few years of the company’s existence raising money and chasing scale. When the market turned, we realised we hadn’t focused enough on overheads and other operational costs. The downturn forced us to radically optimise the business and increase operational efficiency. We squeezed our way through the downturn, came out showing fantastic unit economics and today we are a better company for it. We have instilled a discipline of running a tight organisation giving us the ability to flex our marketing spend to drive scale when times are good and pull back this spend and allow product innovation to drive growth during tough times.

At Lightbox, we avoid businesses whose main differentiator is the amount of capital they can raise. That being said, we think a lot about the role of capital in a business and the advantage that can be created if you can raise capital and hoard it. Just because someone is willing to give you a lot of money to realise your dreams, doesn’t mean you need to spend it all right away. We work with our portfolio during the upturn to raise as much money as we can and not spend it. Productivity software firm Slack raised $160MM in April of this year bringing the total capital raised to nearly $300MM. CEO Stuart Butterfield, commented, “We have decades and decades of runway.” That’s an amazing position to be in.

Downturns are inevitable. Companies need to have a defensible product-led business. They need to use the good times to build a business that can weather the downturn. With these two principles in place, when the times get tough they can hire aggressively, acquire customers cost-effectively and out-innovate competition thereby using the downturn to truly accelerate and secure a leadership position.

About the author:

As an early investor in InMobi and InfoEdge, two of India's billion dollar technology unicorns, Sandeep Murthy is one of the builders of India’s Internet economy. And he hasn't just seen the highs and lows play out as an investor, but has actually roughed it out in operational roles including one as the CEO of Cleartrip in 2006 for two years. Today he's a co-founder and partner at Lightbox, a VC firm based in Mumbai.

(image credit: ShutterStock)