Can Indian startups break the Great Wall of China?

Remember Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation? When actor Bob Harris (played by Bill Murray) arrives in Tokyo for a shoot, and he is lost –literally – in a new language. He is unable to express the emotions for the advertisement that he is shooting, because the translator says in a sentence what the Japanese director explains in ten.

The film is easily relatable to anyone who has been stranded in a city where you have no friends, cannot follow the native tongue, and are unfamiliar with the local culture. What if you want to do business in such a place? In Asia, that place is likely to be China – the world’s second-largest economy - which the rest of the world finds hard to enter. Infamous for its censorship and strict regulations, China has so far kept even the US giants such as Google and Facebook away.

So far, other than mobile advertisement platform InMobi, Indian startups that went abroad have kept away from China. Hostel chain Zostel went to Vietnam in August 2015, and logistics focused data analytics startup LogiNext launched their services in Singapore six months ago. Doctor-appointment platform Practo also ventured into Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Philippines last year. But China’s wall against foreign entrepreneurs remains as strong as ever. Can Indian startups succeed in a market that is tough, but worth the hard work?

Why China is important to India

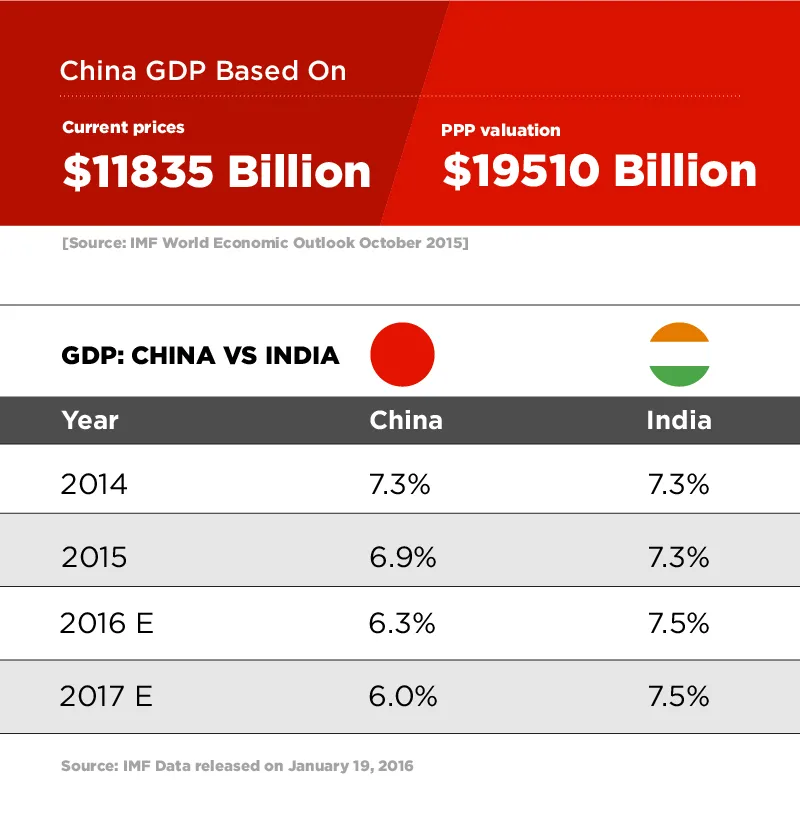

China is India’s largest trading manufacturer – but export to China from India was only worth $14.8 billion, whereas that from China to India was $51 billion in 2015. However, Chinese VC firms and enterprises have been keen to invest in Indian startups. In fact, during 2014-15, $72 billion worth of investments were made by China in India. This included funding from Ctrip in Makemytrip; Alibaba in Snapdeal and Paytm; Didi Kuaidi in Ola; and Tencent in Practo. More investments are in the pipeline: Baidu is considering investment in Zomato, Bookymyshow, and Big Basket; Cheetah Mobile has planned 20 transactions over the next three years in sectors that will increase traffic on mobile Internet and enhance their monetising capability. Alex Yao, Senior Vice President of Cheetah Mobile, has told YourStory that they are focusing on startups that can provide any local content that would potentially move from offline to online.

According to a report by McKinsey & Company, the rapidly growing upper-middle class will drive consumer spending in China over the next decade. In 2012, the upper-middle class made up 14 per cent of urban households; by 2022, that number is expected to rise to 54 per cent. China, being home to the largest number of smartphone users in the world, also attracts tech-based startups.

Like India, China is a mobile-first country. China overshadows India as a market for mobile-focussed businesses. Jessie Yang, Senior Vice President, InMobi China, told YourStory, “Users have moved their consumption largely to mobile, so much so that even the payment infrastructure in the country is dominated by mobile wallets – a sector in which India has a lot of catching up to do.” InMobi is already the largest mobile advertising platform in China.

Hurdles for foreign businesses in China

China is not the most welcoming country for outsiders. No American companies – which have succeeded elsewhere in the world - have made it in China. Exceptions could be Apple, Uber, and Starbucks– but even they have had to pay their price. Uber, in fact, is reportedly losing more than $1 billion per year in China due to the immense competition from Didi Kuaidi.

Government censorship and complicated regulations have been tough against foreign enterprises in China. Google, the search engine that rules the world, leaving China in 2010 stands testimony to the fact that the government will always have the final word. Although Google had censored search results for four years, they gave up on China after a cyber-attack on it. Baidu’s success shows that Google was not really missed.

Messaging app WhatsApp also met with a similar fate in China. Unlike their competitor WeChat, which is subject to Chinese laws, WhatsApp is pro-privacy. Even the world’s most popular social networking website, Facebook, was banned by the government in 2009. (whether its new app, which claims to evade all censorship, will make a change is yet to be seen.) However, professional networking site LinkedIn wrote a different story in China by complying with the government’s demands and adhering to censorship laws.

But one shall not miss out on the difficulties a startup (as against giants like Google and Facebook) would face in China. When Mumbai-based LogiNext was launched in 2013, co-founders Dhruvil Sanghvi and Manisha Raisinghani went to China to explore the market. But the ground realities they learnt from their month-long stay in China dissuaded them from entering the market. Without Google Maps, and Baidu being available only in Chinese, they were literally lost. “I had to call my friend in India, and he sent me a laptop with VPN installed. So I could search on Baidu and translate via Google,” says Dhruvil. He adds that although Shanghai has a cosmopolitan crowd, in areas where manufacturing happens, practically nobody understands English.

Why China does not need the world

In China, where e-commerce accounts for about one-tenth of all retail sales, Alibaba continues to have a greater reach than Amazon, although it has been more than a decade since the latter’s entry. According to Financial Times, WeChat has more than 650 million active monthly users and is catching up rapidly with WhatsApp, which has just passed the billion-user mark. In fact, according to Alex Yao, Chinese startups are becoming more service-oriented. “Online to offline innovation in China is already ahead of the US. Even if our tech capabilities are behind, operational capabilities are way better,” he says.

Many agree that consumer Internet businesses may not be the best sector for Indian startups to enter. A top investor in China, who wishes to remain anonymous, said, “In every sub-sector within consumer Internet, Chinese companies are ahead of their Indian counterparts in terms of scale, penetration of the market, and innovations in the business model. They are also better funded.” Beijing-based mobile Internet firm Cheetah Mobile has 70 per cent of its user base outside China. “We have a lot more resources than our global peers who are doing the exact same thing as us. Reasonable labour prices, a fund-raising environment, and a good supply of tech talent, are other factors,” says Alex Yao.

Chinese user habits are different from Indians, and startups need to understand those and act accordingly. Founder and CEO of smartphone manufacturer One Plus, Pete Lau, says that the product bar is set very high. “Companies entering China should ask themselves how the user experience offered by them is really different from the experience already present,” he adds.

Watch out, startups

Understanding the Chinese market takes effort as their cultural nuances are crucial. According to InMobi, China has a strong ethical and cultural heritage. “The Chinese have a strong hierarchical aspect to society and business. Communication must focus on a ‘top-down’ approach rather than a ‘bottom-up’ one,” says InMobi's Jessie Yang.

Qualified resources and on-the-ground support are also essential to scale in China. India-based AddedSport, – a sports management firm – has successfully established itself in China along with the Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore. Founder Akshay Maliwal says that Indian businesses in China will need to find qualified Chinese partners they can trust. “Make sure your IP is protected and used in the right way. The biggest challenge is the understanding of the pain points of Chinese consumers,” he adds.

However, InMobi believes that hiring the best local talent and giving them free reign worked like magic. “We could have either gone for a joint venture with a company established in China that is aligned with InMobi’s goals or gone independently and hired local talent,” says Jessie Yang. Although a joint venture would have provided insights into the nature of the Chinese market, it might affect your independence and flexibility. On the other hand, going independently would mean applying for a licence, which might take six months. “We opted to go independently, which might have looked like an unsafe bet to most people. But you end up spending far more time identifying, approaching and partnering with a Chinese company than it would take to secure a licence independently,” she says. Besides the flexibility and freedom that operating independently provides, hiring local talent has paid rich dividends, she adds.

According to Karthik Prabhakar, Vice President at IDG Ventures India, the consumer market in India is a replica of what happened in China earlier. “Indian companies have a less competitive edge; so enterprise solution is a better choice,” he says. Indian startups also need to focus on local consumer demand, warns Alex Yao. “Trends in China can fade away in six months,” he says, adding that media-oriented businesses find it harder compared with transaction-based businesses.

Is India enough?

When Pete Lau first met with Amazon India CEO Amit Agarwal, the first part of the conversation revolved around company philosophy and culture. Once they saw the alignment, everything else fell into place. “The Chinese maintain these philosophies and culture across regions,” Pete Lau says.

Entering China is inevitable for anyone who wants to have a global footprint. If Pete Lau is right, a strong understanding of local culture can help Indian businesses crack the Chinese market. Karthik Prabhakar believes that infrastructure-oriented businesses and SaaS-based solutions can still find some market in China from India.

However, it is not to be forgotten that India has immense scope for growth. With better infrastructure and Internet penetration, e-commerce and transport are bound to improve. According to the investor mentioned earlier, the India market itself is not very easy to crack if you are a young company, and entering China will divide their focus. e-Commerce unicorn Snapdeal, funded by Chinese giant Alibaba, agrees. A spokesperson said: “India is a consumption-driven economy, with total consumption amounting to 70 per cent of the GDP. We believe that 10 per cent of consumption spends will move online and that is a huge opportunity. Our current focus is on bringing the next 100 million Indians online, and driving digital habits among our users."

Of course, once you grab one market locally, it is easy to enter and succeed in emerging ones.

However, things could change in the near future, and greatly so. India and China had the same GDP in 2015- 6.9. While is it a decent number for India, it waa a 25-year low for China. (In 2014, China’s economic growth rate was 7.3 per cent). It may not be too long before China open its gates to the rest of the world for more ideas and better technology. In fact, the key for LinkedIn’s success really was that there is no substitute for their website in Chinese – not even with Baidu, WeChat, and Weibo put together. And that is exactly the lesson here - there are 1.7 billion people in China; give them something they have not thought of yet.