Employee value proposition at startups: Why and how is it different?

Water cooler conversations, government announcements, and media stories share a key theme: startup organisations. The success of unicorns like Flipkart, Snapdeal, Ola, Paytm, and Zomato (amongst others) has gone on to amplify the romance of the next big idea.

Over the last couple of years, we were fortunate to work with some of the brightest and most enthusiastic minds in the Indian startup landscape. And while everyone admitted that addressing people concerns was a major consideration – and often at a par with (if not larger) than product development, marketing, and raising capital – no one had a definitive answer on the best approach.

Consider the following two examples

To a startup founder, a major aspect (and therefore risk) of the entrepreneurial journey is about partnering with the right people. This includes not only the people who invest in the big idea (or the sample users who decide to try out the pilot product), but also the team the founder hires. A large Indian e-commerce organisation was riding a wave of aggressive growth backed by successive rounds of funding. Growth meant more people. Soon, there was a large and diverse workforce with complex people issues. It was felt that a common cultural context needed to be defined. The process was initiated. But it was a reactive response, with the organisation playing ‘catch-up’ and losing high performers with great potential.

A niche Bengaluru-based startup – with a garage office, garden chair meeting ‘room’, etc. —raised a limited amount of angel funding. The first thing the founders did was to sort out long-term rewards for their team of 20 odd employees, even worrying about the culture they were building. Notwithstanding their growth plans, the founders were clear: they had the best people they could have possibly employed and so, they needed to keep the group together. But it was about long-term value, not cash alone.

Both examples highlight organisations that recognised the need to address people issues, but at different stages of their evolution. This determined the way they responded, one reacted while the other planned ahead.

The employee value proposition for a startup

For a startup founder, the idea of creating something bigger than the individual is not easy to sell to an 'employee'. Even then, it is perhaps easier to do so for the first set of hires – the ‘legacy’ hires – acquaintances and people they have worked alongside and are comfortable with. It is the next round of hires with whom this becomes difficult. In other words, the commitment resulting from the ‘big idea’ is difficult to sustain over time.

And so, the founder has to offer her/his employees something which goes beyond the proverbial pot of gold. This is also why the employee value proposition (EVP) – the set of experiences that help keep employees engaged and motivated – occupies significant founder mindshare: acknowledged, actioned or otherwise.

While we often joke that startup founders are men and women in a hurry, it can be true. And so, a very specific EVP is what they are interested in and have time for. In our experience, this translates to a mix of the following:

- Financial rewards (cash, equity, a chance at a lifetime of wealth).

- Behavioural identifiers (a larger cause, impact and recognition, thrill, freedom to do your own thing).

- Lifestyle choices (flexibility and wellness).

- Development opportunities (career growth, diversity of roles, the novelty of work, learning to startup).

At the same time, the EVP cannot be static. It will depend on how the founder balances (and so, focuses on) the considerations of purpose (and goals), funding and investor returns, and organisation (and culture). We have found that different combinations of these three considerations help outline broad contexts or frameworks within which an organisation’s EVP can be established.

The three most commonly observed EVP frameworks for startups

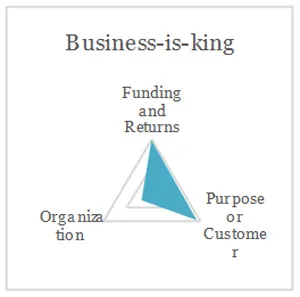

The first (and most common) case is when business growth/goals and funding are key considerations for the founder(s). Such business-is-king startups focus on market-aligning or even market-leading pay and designations through finely-tuned performance metrics. Individual development is driven by business strategy and these metrics. Individuals are expected to build the required skills and adapt. Often, such startups leverage equity or long-term incentives as a retention hook.

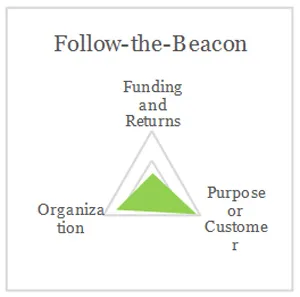

Next is the case of the follow-the-beacon startups, where there is a balance between the purpose (and this could be the customer as well) and organisation considerations. These organisations offer moderately competitive pay, but also focus on a game-changing idea, freedom of expression, and participation in decision-making as core cultural values. It is not only metric-based performance, but corporate citizenship and the demonstration of expected behaviours as well, which drive rewards.

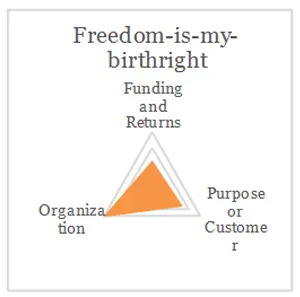

And finally, there are the (relatively fewer) examples of the freedom-is-my-birthright startups, where organisation is the primary consideration for the founder(s). Such companies pay a significant amount of importance to flexibility. They create opportunities for their employees to collaborate. Many of them pay for skills through project-based or contract-based models. In turn, employees develop skills in keeping with their own likings/interests.

In conclusion

For any entrepreneur reading this article, the idea of the EVP should not come as a surprise. As a founder we spoke with underlined, ‘We start thinking about people issues from day one. Not everybody plans to address them in time.’

The first (and easier) option is often to look at using new funding to address people issues by focusing on pay corrections. While the arguments in favour of doing so are manifold, there needs to be a plan, on how funds should be spent. Upping pay alone is not a sustainable answer. There is always the investor, who will see the sudden spike in employee/pay-related expenses and will press harder for results. It’s a difficult spiral to climb out of.

This is where the EVP comes into play. It needs to be specific and contextual to the company, the market, and the business model. And most of all, it needs to evolve. With time and the founders’ focus.

About the authors

Abhishek Mohanty (left) is an Associate Director with

PwC’s People & Organisation

practice. He holds a Masters in Business Administration from the Xavier Institute of Management, Bhubaneswar and a degree in Economics from Hindu College, Delhi University. Viraj Patil (right) is a Senior Consultant with PwC’s People & Organisation practice. He holds an a Masters in Business Administration from the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore and an engineering degree from M.S. Ramaiah Institute of Technology, Bangalore. Together, they have worked with clients (corporates and startups) across industries and sectors in areas such as organisation structure, performance and productivity, rewards and talent management. Both of them are based at PwC’s Bengaluru office.