Creating and sustaining a unique culture at a startup

A few months ago when we met the founders of a startup and observed them looking at predictive analytics solutions, we were pleasantly surprised to hear them talk about their startup’s culture (often considered a nebulous subject and low on the priority list for startup leaders) as one of their primary concerns.

“We begin thinking about people right from day one. The first task is to get people on board with our big idea. And it is usually folks we know – legacy recruits – with whom we share a certain degree of connect, comfort and trust. But it is the next round of hiring where it starts getting difficult because it is not just the big idea anymore. And so, as we grow larger, the people-related question goes from being one of hiring to that of culture.”

Our first takeaway from the conversation was that the startup talent ecosystem isn’t altogether very different. Like any other institution, a startup has employees, and employees eventually look for rewards, well-defined processes and development opportunities.

Secondly, founders worry about growth as much as they do about how their vision (which made them and their initial hires believe in the big idea in the first place) can be sustained. The answer to this is usually attributed to the organisation’s culture.

On the whole, this is what a founder, leader often refers to as culture: The force that powers growth without having to ‘resell’ the big idea. This idea of ‘culture’ is driven by a deep personal conviction; it is unique to her/his organisation – meriting a custom approach to sustain it with growth and time. And since every new hire is that much removed from the founder/leader’s beliefs, this unique culture needs to be reinforced.

So how do you build and enable an intentional culture?

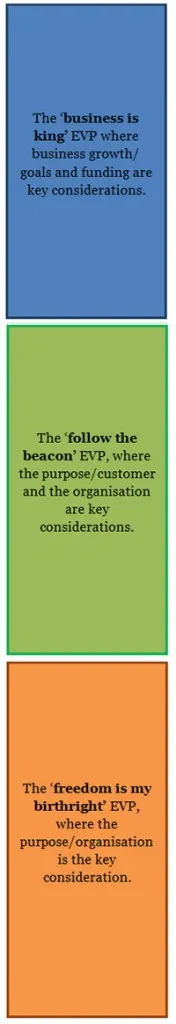

In our previous article, we spoke about the employee value proposition (EVP) in startup organisations and proposed three commonly observed frameworks (business is king, follow the beacon and freedom is my birthright), depending upon how the founder/leader chooses to balance considerations of purpose, funding and investor returns, and organisation. And since these frameworks reflect the founder-leader’s beliefs and choices, they can help identify artefacts, enablers and processes to build and reiterate the desired culture.

The cultural context here is then one of metrics-driven performance and rewards. And as the organisation grows, it must put in place enablers such as the following:

- Processes not just for spotting high performance but innovation as well.

- A total rewards strategy that not only leverages equity but also takes care of health, pensions and other benefits.

- Human capital policies and processes that are agile and evolve with the organisation’s growth and demand.

- Governance and compliance – otherwise often the first casualties of hyper-growth.

A shared belief on and a collective push towards the next game-changing idea suggests an environment that allows for corporate citizenship and participation in the decision-making as the core cultural constructs. Employees are self-driven towards the shared purpose as this purpose is no longer an altruistic statement but a business imperative.

In this context, the organisation relies less on the pay and more on enablers which incentivise expected behaviours through the following:

- Opportunities for continuous learning and development and work which challenges employees and provides them a chance to make a difference.

- Performance management which talks about the incumbents’ competence as opposed to the defined role descriptions. At times, the tools to achieve this include purpose-focussed events (for example, hackathons) and gamification of desired behaviours.

- Shared, articulated values that are reinforced through rewards.

Flexibility, autonomy and varied challenges in return for working on a short-term contractual basis is the proposition offered by the third archetype (freedom is my birthright) of startups. These are typically complex, organically growing startups of specialists that compete for skills. Pay plays a minor role. Even the human resource function serves the role of a policy regulator rather than a resource manager.

The cultural construct is one of choice, and by implication, one which allows individuals the freedom or flexibility to choose their work portfolio. As a result, there are no career paths but a variety of challenges and roles. Think freelancing or employment for a specified contract. Possible enablers for these startups could be as follows:

- A talent marketplace which allows members a chance to create their own personal brand and sell their own skills. Here, individuals work on their reputation (as the seller of skills), while the startup brands the opportunities on offer.

- In turn, the pay varies with the demand and supply for skills (much like airline fares).

- If such a startup is an incubated venture within a larger organisation, then there is an unstated need to isolate the startup from all policy and process decisions. Sometimes, not co-locating the two helps.

Conclusion

Culture in a startup is a vital contributor to the entrepreneurial formula. It is what distinguishes a startup from a more established organisation. And so losing the culture, which made it distinct in the first place, is a problem founders/leaders grapple with as their organisations grow.

This concern is also not about not evolving. For example, in the beginning a startup may simply not have clearly defined processes like ‘onboarding’, and specific teams take up the responsibility to assimilate employees. However, with growth, there is a need to put in place these processes, otherwise the growth (and the business) cannot be sustained. Some founder/leaders use mechanisms like structurally separating teams into independent businesses so that the culture of a startup is retained. Others make sure that the metrics of performance are entrepreneurial in nature, for example metrics that focus on customer delight rather than the throughput.

Finally, growth begets the question that the founder/leader must also take a call on when the startup ceases to be a startup. In other words, there is a definitive critical mass which it attains, when the more traditional processes and structures need to be introduced.

About the authors

(left) is an Associate Director with PwC’s People & Organisation practice. He holds a Masters in Business Administration from the Xavier Institute of Management, Bhubaneswar and a degree in Economics from Hindu College, Delhi University. Viraj Patil (right) is a Senior Consultant with PwC’s People & Organisation practice. He holds an a Masters in Business Administration from the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore and an engineering degree from M.S. Ramaiah Institute of Technology, Bangalore. Together, they have worked with clients (corporates and startups) across industries and sectors in areas such as organisation structure, performance and productivity, rewards and talent management. Both of them are based at PwC’s Bengaluru office.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)