Behind-the-scenes of how e-commerce delivers your bulky shipments

While it is as easy as spending a few minutes online to place an order for a washing machine, the kind of work and resources that go into getting it delivered and installed at your home in time is no joke. From the minute you confirm an order, about seven persons are involved in ensuring timely delivery.

The toughest part, predictably, is the actual transportation. For e-commerce players, working out the logistics for bulky items is among their biggest challenges. If cash burn is a part and parcel of e-commerce, logistics is the fuel.

A report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch in 2015 stated that the e-commerce market in India will be worth $220 billion by 2025. With growth in sales, delivery process gains significance. Although Ecom Express, Delhivery, Ekart and Gojavas have established themselves, the surface network is yet to grow. YourStory finds out more.

Different categories, charges

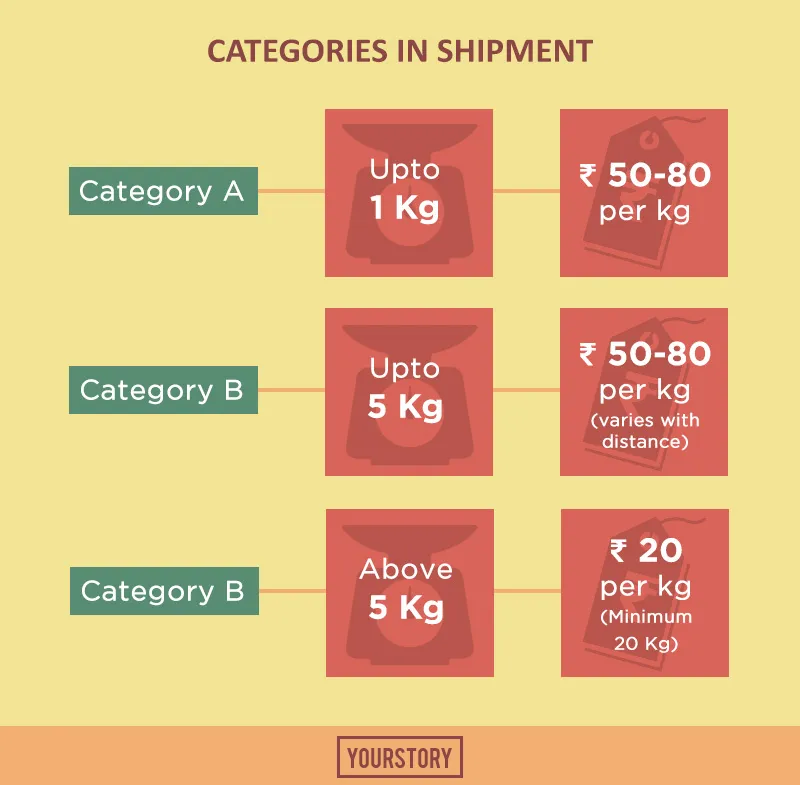

For supply chain, items are divided according to size- Normal and Large. Home appliances and furniture are Large, and everything else in Normal. Apparels, books, electronics etc., which fall in the Normal category, follow the inventory model, while Large items are delivered hyperlocally.

The shipment charges are made according to the weight of the package, not the item. Volumetric weight is more than the actual weight of the parcel. When a 5kg chair is packed, it can weigh 30kg. Charges vary with distance: a local delivery is around Rs 30 per kg; Rs 80-90 for zones, and national is Rs 100-130.

Dedicated trips from fulfillment centre to the drop point are essential for large items. But logistics companies want a minimum commitment. So even a shipment of 20kg will be charged as one with 50kg, which is their minimum requirement for running a vehicle. But this is not financially feasible for the client.

Demand for more efforts

Most logistics companies focus on smaller packages via air transport. Ajay Rao, Founder and CEO of Emiza Supply Chain Company, says that 50-70 percent items are shipped by air today, and last mile by bike. There is more interest on large items now; but for that, these networks won’t work. He adds, “We need dedicated fleets of vehicles and a strong surface network.”

Full truck load is significant here. Ajay says that only 33 percent are heavy or medium commercial vehicles. “Some players are already doing less-than-a-truck [load] on a primary route in secondary and tertiary market. In short inter-city or intra city routes, there is a shortage of good service providers handling less-loaded trucks,” he adds.

Full trucks minimise the movement, and hence prevent breakage despite bumpy roads. But the poor condition of highways demands efficient packaging to protect the goods, leading to higher packaging costs.

Shobhit Jain, Head of Delivery, Vulcan Express, says that the network will choke in terms of costs and service if one pushes in more volume than the designed capacity. To ensure that the van capacity is utilised optimally, Vulcan Express runs optimisation software. Shobhit explains, “Both Knapsack and travelling placement problems are thus solved simultaneously. It can know the time of delivery by looking at the traffic. For instance, if a vehicle can touch eight points today ideally, it will most probably be over capacity. So it can be six points with full capacity, or eight points with sub-optimal capacity. We plan the vehicle load based on these optimisations.”

Challenges in infrastructure and topography

Customer expectations are different for large items. For a TV or a refrigerator, the delivery boy has to come at a time convenient for them and do the installation. This demands specific training of personnel. Every step has its own challenges: weather conditions, manpower availability, and poor pincode mapping among them.

Neeraj Agarwal, VP, Operations at Flipkart, says, “Rainfall and floods affect delivery even in metro cities. Some delivery boys were stuck on the road for 5-6 hours in Gurgaon during the rains last month.” Hyperlocal model, hence, is ideal for large items. Many e-commerce companies are doing geo-tagging to ensure that the supply of Category C (large) items is located as close to the buyer as possible.

Warehouse capabilities

Warehouse layout and storage mechanism also varies between categories: For Categories A and B, shelves are tiered, with three to five floors of racks where people can walk in and pick up goods. Category C has pallet-wise storage and different automation technology. Even the personnel have to be trained separately in packing and handling. For furniture, due to its bulky nature, the warehouse also has to accommodate huge loading and unloading equipment.

Warehouses usually have a more contained environment and are less prone to run into external issues as last-mile operations. But if there is an Internet shutdown, it can affect the warehouses’ functioning for hours. Neeraj of Ekart says, “Warehouse staff needs to ensure zero errors, so that the item won’t end up in a wrong geography or with a wrong customer. Long-haul network traffic should be transparent. Our technology for tracking is very precise.”

For high-ticket products in Category B too, warehouses take extra measures. Gaurav Khushwaha, CEO and Co-founder of online jewellery platform BlueStone, says, “We have created standard operating procedures specifically for fine jewellery. Everything that happens in each department is captured in cameras. If there is a leakage, we can pinpoint where it happened.”

Alternative model

Any inventory-led business model inevitably faces warehouse issues. But online interior design platform Livspace has no such issues. Co-founder and CEO Anuj Srivastava says, “We are not inventory-led, as 75 percent of what we do is manufactured by contract. So handing and, hence, breakage is minimal and so is the return rate.”

However, cost of packing bulky items is about six percent more. “The padding material we use is more sophisticated than what is used for books or electronics. In intercity [for raw material transfer] maximum space is utilised for packaging. Because the size of the order is larger, with 100-150 times stacked up, you can pack more items in the same truck. For a small truck, it would be tightly packed and, hence, low movement, which means lesser leakage.”

Online custom furniture store Woodenstreet’s CEO Lokendra Ranawat says that every material used for packaging is 80-percent resistant towards major environmental conditions. “The biggest challenge you face with reverse logistics is the packaging. It is quite difficult to bring back the product in the same condition as it was dispatched due to lack of materials at the location, which ultimately results in an increase of damage,” he adds.

Need of the hour

Pain points present opportunities. The present need is the capability to build a decent B2C supply chain. About 15 percent of all e-commerce shipments are in Category C. Manish Saighal, Managing Director at Alvarez and Marsel, believes that traditional Category-A players should build Category-C supply chain too. “There are not many specialised players in Category C now. The network that we need to build for heavier shipment coincides with that of industrial goods. But, globally, this convergence is happening. Some logistics companies have invested in building B2C model for heavier shipments using their line-haul network,” he says.

Of course, a mix of Category A and Category-C products is not possible in the same truck. Vehicles should be dedicated for that particular consignment. Neeraj of Ekart says, “Even if there are two supply chains for Large and Normal categories, wherever there are opportunities to cross-leverage line haul we do it. Since our operations are massive, trucks are always completely loaded.”

Profitability question

To make profit, logistics companies need to go beyond e-commerce and start serving offline sector, which provides more opportunities. Ekart, the logistics arm of Flipkart, recently started catering to other e-commerce players as well as offline retailers, and does P2P courier service too now.

Ajay says that DHL-owned BlueDart has done exceptionally well in e-commerce too because they already had an established courier network serving B2B, including their own aircrafts. He suggests that for logistics networks to get the full benefit of implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST), surface transportation has to become dominant.

“Government should avoid taxation document checks and open up State borders. Transportation, quality, speed, accuracy of surface transportation will improve then,” he adds.

Profitability surely is the game changer – as was proven by the death of Parcelled and pivoting of online grocer Peppertap to focus on logistics. Manish of Alvarez and Marsel believes that GST will encourage many B2B companies to move into B2C movement too. A telling sign is the recent acquisition of e-commerce logistics firm Gojavas by traditional services provider Pigeon Express.

Room for improvement

There is surely a lot of room for improvement for logistics infrastructure in India. Compared to the US, condition of Indian roads is poor and logistics processes have to be more tech-enabled. Lokendra of Woodenstreet says, “They have better and well-equipped transporters with double stacking facility, besides better loading and unloading equipment, which we lack.” Although Woodenstreet delivers across all major cities, a few suburbs are avoided as damage is a surety.

With the rise of dependence on e-commerce, there is a pressing need for the logistics sector to be more organised. Neeraj of Ekart believes that in the next 10 years, logistics could become the country’s biggest industry. “Driven by the growth of e-commerce, in the last three years, it has become more demanding. Estimated at $100-110 billion now, its organised sector is only a small fraction. In three years it will be $300 billion,” he says.

With more players entering the organised sector assisted by tech, the current truckload capabilities can be improved to a great extent. Automation is the key, and the next generation of logistics players have to find it in their technology.