Karnataka’s farmers will have to produce marketable quality to gain from pioneering reforms

Manoj Rajan has plenty on his hands. He has three visiting cards for the three hats he is wearing. He gets a call from a district collector, and he discloses it sotto voce. He has to make a presentation in Delhi and the secret is shared. Karnataka’s cultivators are “my farmers.” It is clear Rajan has a sense of ownership.

The quirks of the MD & CEO of Rashtriya e-Markets Services (ReMS) aside, his enthusiasm for the project he is executing is evident. His manner is mobile; it varies for emphasis. From his voice, it seems, he sees a crowd in the lone face across the table. He is determined to convince.

Without that will, shifting Karnataka’s agricultural produce trading platforms from open cry to electronic against opposition from traders and brokers would have been difficult. Rajan has been able to push it through. He is wary of claiming success. Progress in some mandis has been better than in others. It will take about a year for the system to “stabilize”, he says.

Three things worked against farmers in the earlier system. Competition was limited to local traders in a mandi making it easy to collude. Farmers did not know the prevailing prices. The bidding was opaque. A trader with a couple of goons in tow, for instance, could silence higher bidders. Prices would be rigged with eye signals. Farmers did not bother about quality because prices did not match them. Traders would routinely make deductions for poor quality, often falsely, so farmers had little incentive to offer better. They would, say, moisten cotton or add stones in gram to increase their weight. Short weighing was routine. Chits of paper substituted for formal bills.

Unlike the electronic National Agricultural Market (e-NAM) project, Karnataka has attempted root and branch change. Technology is one aspect; the process itself has been overhauled. It began in 2013 with a committee giving a blueprint for reform and an announcement in the state budget. The law was amended, the rules were notified and in January 2014, ReMS was incorporated as a joint venture between the state government and the National Derivatives and Commodity Exchange (NCDEX). Execution began from the next month.

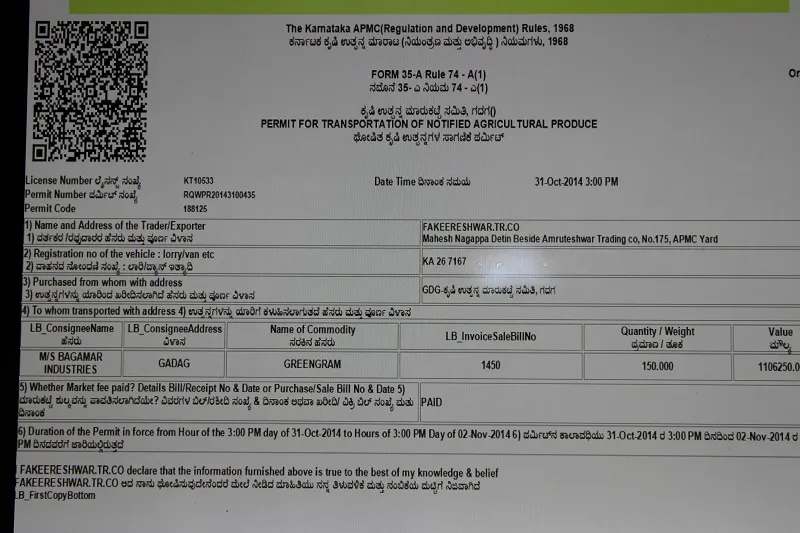

When a farmer arrives at the marketing yard, an entry slip with his name and mobile number is generated. The lot of weighed electronically. A farmer has the option of selling the stuff directly to a person of his choice or putting it for auction through a commission agent. A sample goes for assaying, which ReMS does free for farmers in 40 mandis. About 30 more are in line. It is being done for 20 of 42 commodities traders. Costly automatic grading and cleaning machines are also being installed.

Parameters like moisture, defects and foreign matter content are noted and a certificate is given. Currently this is done by National Collateral Management Corporation. To ensure that the assayer does a faithful job, certificates are randomly audited by a third-party with control samples. The information is posted on the trading platform and the bidding starts. An SMS of the highest quote is sent to the farmer who can elect to accept it within half an hour. Once the assent is given, a bill is generated and payment is made in cash or directly into the bank accounts, if they are registered for it.

Suresh Dasanapur of Hubbali district calls it “volleya (good) project.” He is a big farmer, owing 110 acres, and a former president of the district’s mandi. Most of the farmers selling produce at the yard have registered for online payments, but small farmers crib, he says. They want to be paid in cash.

Terming the trading “tumba chennagide (very good),” Devaraju BS of Tiptur in Tumakuru district says trading at the copra mandi is online, but only a miniscule number of trades end up in online payments. He blames “lobbies” but V S Rajanna, the district’s Deputy Director, Agriculture Marketing says aspects like traders not getting credit lines from banks are holding back that reform Last year, of Rs 700 cr payments made, only Rs 1.70 cr or a quarter of one percent was paid directly through banks. He expects change to gain pace over the next few months.

As of now 151 of the state’s 158 mandis have shifted over. Their traders can bid for produce in any of them with a single license. About 150 bulk buyers like Metro Cash-N-Carry, Cargill and Godrej have enrolled. Scientifically-managed warehouses have been notified as sub-market yards where regulated trading can happen as in the main yards, so farmers do not have to lug produce over long distances.

With increased competition farmers are supposed to get a higher share of the consumer price. “This is the litmus test of whether reforms have happened or not,” says Rajan.

He cites examples. Year before last, tur or pigeonpea prices per quintal in the Yadgir market (Rs 4,113 on average) trailed those in Gulbarga (Rs 4,245). Both were offline then. Last year, after it went online prices in Yadgir were Rs 5,200 ─ Rs 300 higher than in Gulbarga, which has resisted change.

Turmeric traders from Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu are shifting from Erode to Chamrajnagar. Rajan says. Arrivals have increased four-fold from 23,811 quintals in 2013-14 to 100,511 quintal in 2014-15 despite no expansion in growing area. Prices between the two markets have narrowed to a sliver.

The state did not do minimum support price intervention in copra this year, unlike in neighbouring states, because rates in Karnataka mandis were higher than the MSP.

The 27 lakh farmers who have registered get SMS quotes. They can also dial a call centre. Traders do not have to wait for markets to open the next day and unnecessarily incur overnight truck charges. An online ledger system with credits and debits allows them to take produce out of their mandi godowns after market hours. Facilities like toilets, drinking water and waiting rooms have also been provided.

Andrew John has been trading in tamarind at the Tumakuri mandi for 41 years. He buys in bulk and exports in retail packs to West Asia and Europe. John says “Yes, this is definitely an improvement,’ over the earlier tender system. “In the tender system there used to be some understanding between traders and commission agents. Now there is absolutely no doubt which is the highest bid.”

Panduranga R, of Turuvere village in Tumakuru district says traders have been forced to use electronic scales after protests by farmers like him. Earlier, they used to filch about half-a-kg to 1 kg per bag (30 kg) of tamarind.

Gopal Naik, Chair for Economics and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, says it is essential for farmers to produce marketable stuff to be able to sell across the state. Producing to prescribed quality standards is essential. We have neglected standardization, he says. ‘Over time, we have not told farmers what the market is looking for.” National standards have also become obsolete. Naik was a member of the reforms blueprint committee.

Rajan says ReMS is preparing standards based on 25,000 samples. It wishes to communicate that earnings rise more than proportionately with better quality. For instance, groundnut with moisture content of 18-20 percent fetched Rs 3,170 a quintal but when reduced to 4-6 percent, the price rose to Rs 5,244, a gain of more than Rs 2000, on a small loss of weight.

Naik says progress has been slow. E-tendering has been implemented but other aspects are taking time. Traders and brokers are resisting as they have much to lose.

Rajan wants to expand the number of farmers who have gained. A big communication exercise has been launched. . A large constituency of gainers invested in reform must be created so that reforms are not rolled back. For that the person at the top will have to have drive and a sense of ownership.