Why the unit economics of Flipkart (and competitors) will not work for another decade

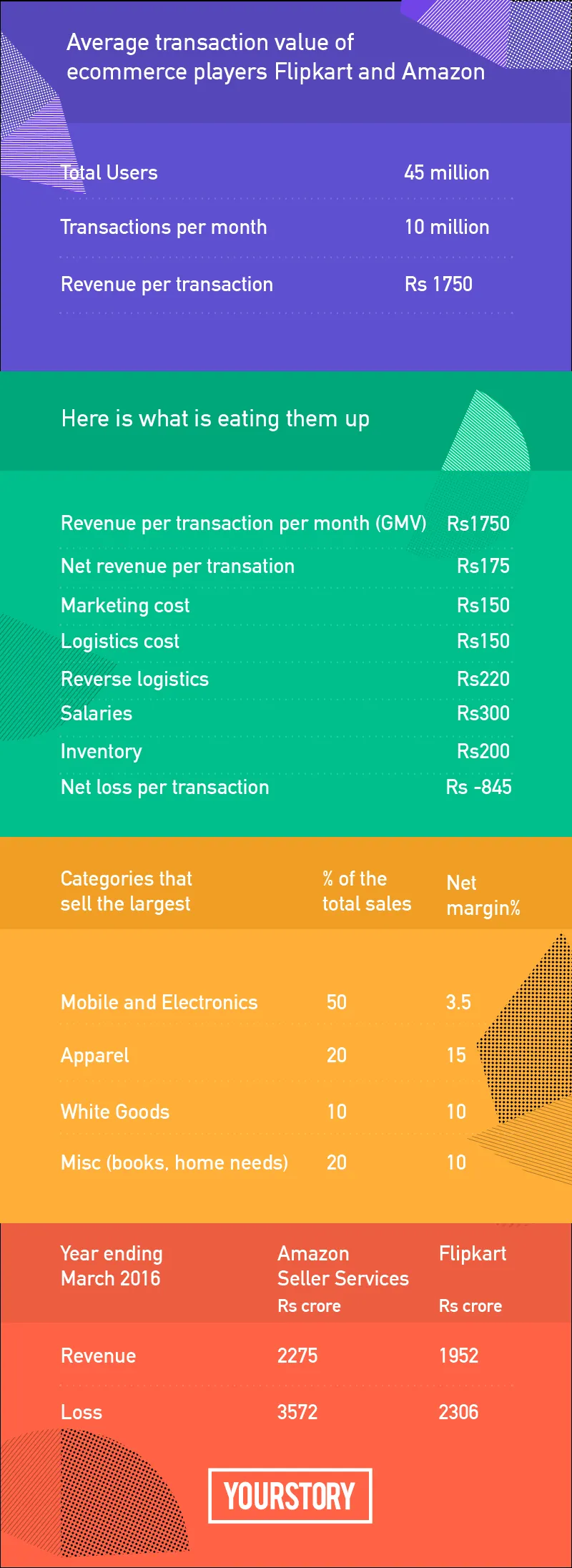

For Rs 175 in net revenue per transaction per month, Flipkart and Amazon India burn five times more money, or Rs 845 per transaction to keep their operations up and running.

If you think you have an idea about the Indian e-commerce industry and how and why it’s bleeding, you are dead wrong. Recently, a logistics company picked up an LED TV from a seller in Bengaluru and took it straight to the warehouse of a large e-commerce company. There, the product was about to be processed for delivery when the e-commerce company noticed a sign saying “Property of the Government”. The entire operations team in the warehouse panicked and picked a fight with the logistics company. The logistic company retorted by saying that its duty was only to pick up the product and deliver it to a warehouse, and not to verify the seller.

The two teams reached out to the seller, who confessed that he had purchased the product from a government office. Now, what happened after, whether the seller was reprimanded or whether there was a scam in a government office that went unnoticed, no one knows. But what was certain was that the cost of managing the logistics and the manpower to move that LED TV was simply too high. Now, these are the complications a marketplace gets into.

This incident, narrated by the logistics firm, which did not want to be identified, told YourStory that the nature of the beast, Indian market conditions, would burn e-commerce companies to the ground if they do not get their operational efficiencies in order.

Crazy sellers, moody consumers, and puzzling regulations, along with the prodigal habits, have made the Indian e-commerce industry burn five times the net revenue made per transaction. YourStory spoke to distributors, retailers, and brands that sell on the country’s top three e-commerce platforms, and the CEOs, who work with the industry, confirmed that the losses are not going to come down unless the companies increase the average transaction value, or GMV per transaction, to Rs 5,000. Currently, the average GMV per transaction stands at Rs 1,750, with a net income of Rs 175 (see graph). The burn per transaction, meanwhile, is five times, or Rs 845, the net revenue per transaction, and it is going to get worse if the companies do not plug leakages by convincing customers to buy more.

Recently, we saw Snapdeal announce restructuring plans. Then, Flipkart was in the news for holding talks with Tencent and other companies to close a funding round worth $1.7 billion. Amazon India, meanwhile, is marching ahead like an army of ants devouring the market, set on claiming market leadership here. However, in the backdrop of the ongoing drama in the e-commerce space, let us not forget that India is still taking baby steps towards internet-based consumption.

“The last 10 years have been about expansion, winning the customer, and learning from operations. Yes, money has been burnt without thinking about unit economics. Any one can build a Rs 50 crore business if they are given Rs 100 crore,” says Devangshu Dutta, CEO of Third Eyesight, a retail consulting firm.

Perhaps the biggest social engineering that occurred, for the benefit of the internet, was “demonetisation”, which after November 8, 2016, urged people to use smartphones to make payments. The government, together with the National Payments Council of India and the Aadhar biometrics platform, is clearly setting out to boost cashless transactions in the country.

According to the RBI, there are 330 million debit cards and 30 million credit cards in the country that together facilitate 44 million digital transactions per month. This is counting all retail transactions, including those made at point of sale (PoS) machines. Since most Indians have dual bank accounts, the number of debit card transactions could be less than half. Then, the point to note is that most of this shopping is an urban phenomenon, covering around 80 million Indians, half of whom shop on e-commerce websites.

“I meet a lot of young brands that want to sell on the online platform only, and they are going after young Indians who will only shop online,” says Harminder Sahni, Co-founder of Wazir Advisors.

With regard to millennial shopping increasing, it all depends on the growth of per capita income, which is what the fate of the e-commerce industry is tied to. They either have to somehow increase the average revenue per transaction to Rs 5,000 or wait for the per capita income of India to grow.

World Bank statistics show that India’s urban per capita income is now around $2,000, or Rs 1.3 lakh, per annum.

However, 85 percent of the Indian working population, 300 million middle-class workers, who draw such an amount, cannot spare even 1 percent for e-commerce, because they live to save. According to the Ministry of Statistics, the savings rate in India is 31.3 percent of GDP.

The need gap: Road to Rs 5,000 ATV and why it is difficult

The losses of Flipkart and Amazon for the financial year are Rs 2,306 crore and Rs 3,572 crore respectively, and that’s mostly because of the amount they spend on customer acquisition. The number of digital transactions is only going to increase provided there is an increase in per capita income. Apart from this, there are several other challenges too.

The culture: For starters, India is not a unitary culture, and it has thousands of local products catering to local tastes and cultures. These local products are not national brands. One just has to look at the apparel industry for an example of this - you would find more than 200 odd styles and several stock keeping units that make up a store’s inventory. In the West, apparel styles are standardised, and there are very few manufacturers.

Local economies: The e-commerce industry must cater to the local for local economy, which will improve their supply chain efficiencies. Amazon and Flipkart have built up enough data to connect local sellers to consumers in their vicinity. But this form of supply chain is yet to be rolled out completely because until recently, the narrative was to connect a seller in Delhi to a consumer in Chennai. However, they have realised that this does not make operational sense anymore from the viewpoint of logistics and returns management.

“The opportunity to connect retailers to consumers through a platform is a big opportunity. E-commerce is here to stay; we connect more than 10,000 retailers with manufacturers,” says Anish Basu Roy, CEO of Shotang. Flipkart and Amazon have signed more than 200,000 sellers on their platforms. Unfortunately, today, only about 10 percent of those sellers sell on the platform on a consistent basis.

Supply chain: Another point to consider is that the supply chain is complex in India. Even the distribution across states is mired in inefficiency, which everyone hopes that the Goods and Services Tax will address. Although the GST can reduce the bureaucracy of paperwork over time, it will just take away the political power of the states. Hopefully GST it will create free movement of goods across the country and warehouses can get more centralised. According to the annual report of Blue Dart, 17 percent of their revenues come from e-commerce, and the company plans to double its business in the space. “Logistics for e-commerce is getting intelligent, with data about sellers and consumers being plentiful. With the increased use of data and the increase of average transaction value, they will cover the cost of logistics,” says Ankit Sethia, founder of HipShip, a logistics company.

Loyalty programmes: Next, it is essential for e-commerce companies to increase the lifetime value of the customer through loyalty programmes and increase purchases to more than four times a month. Unfortunately, the industry today is busy with cashback programmes, which are not going to win loyalty, rather serving only to burn more money.

Finally, e-commerce and organised retailing will never be able to wipe out the neighbourhood store. There are more than 10 million retailers in India, and the opportunity to get them connected with technology is what several startups are after. Companies like Shotang, Xlogix, StockWise, Snapbizz and Mobisy Technologies are creating business models around working capital efficiency for small retailers. Currently, e-commerce businesses are still ramping up sellers, and hope to reach a million sellers by 2020.

According to Ernst&Young, the size of the retailing industry in the country is around $650 billion, of which organised retailing is around $60 billion. E-commerce currently makes up around 3 percent of the total retailing opportunity.

Getting to Rs 5,000 ATV a month is a task by itself, and this will probably only happen five years from now. And if it does not, several online companies will shut shop.

New age brands love them

No matter how much you say e-commerce is bleeding, there is no questioning that they have created scale in India. An entire generation wants to sell their brands online first.

Brands like Wrogn, Fit&Glow, AVA and MCaffeine have built business around the e-commerce platform.

“The scale offered for brand discovery is very high on e-commerce,” says Vikas Lachhwani, Co-founder of MCaffeine, a personal care brand. He says that his target is people between the ages of 18 and 30. Similarly, AVA, another personal care brand that sells on Big Basket, believes that for mass market products, e-commerce was a great way to be discovered. “Indians are experimenting, and the opportunity to create a national brand in a brand-starved nation like ours is wide open. E-commerce helps us find consumers faster,” says Prithika Parthasarathy, founder of AVA.

One only has to go to Amazon India to discover a challenger brand like Fit&Glow dominating sales with its Apple Cider Vinegar and other personal care products. In less than two years, these brands have been discovered through online platforms. There are also apparels brands like Roadster and Breakbounce that sell solely online.

So, e-commerce may be bleeding, but it is like a train that has picked up steam and is not going to stop because there is simply so much opportunity to roll over. The unit economics may not work out currently, but it is pretty clear that these companies aren’t worrying about any of that just yet, as they are focused on acquiring more customers. This will remain the strategy for the next five years. The company with the deepest pockets is going to survive. However, it might not be a bad idea for them to also focus on the need gaps mentioned here and try to reduce their burn. No wonder Snapdeal is in trouble and Flipkart is trying to raise money soon to keep its story of being India’s first e-commerce company to be valued at a billion dollars alive. But the first e-commerce company in India was fabmall.com, which later became Indiaplaza.com, this company shut down in 2012 because it could not raise funds.