Remembering Issur’s revolution — when a village in Karnataka declared azaadi

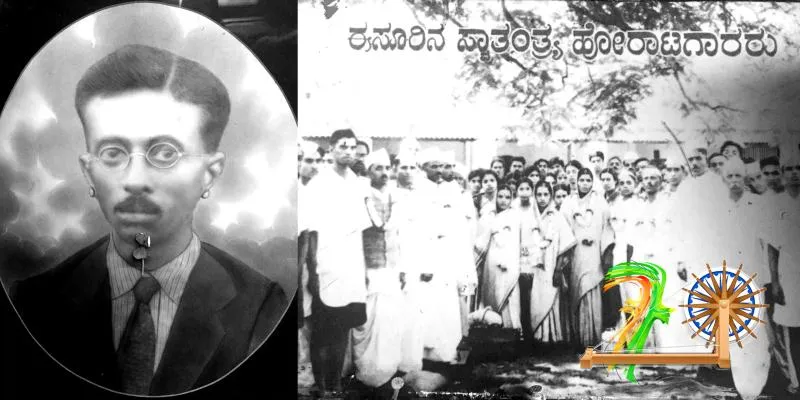

A small hamlet in South Karnataka, Issur is the first village in colonial India to have declared its own independence. Here is a tale of exemplary impudence, when farmers faced the might of the British.

Surrounded by expanses of paddy fields and hills, Issur does not strike as a village that was once a hotbed of rousing violence and vigour. A sense of curiosity precedes as I make my way through the half-empty streets, inquiring directions to Sahukar’s house.

Credited as the first village in India to start a “prati sarkaar” (provisional government) in 1942, the story of Issur’s rebellion is one that took the nation by storm. Such was the audacity of Issur’s revolutionaries that they even penalised British officials who disobeyed their orders and entered the village.

Decades have passed, but tales of Issuru’s brave hearts live on. Their stories of fearless sacrifice are now proudly shared by second and third generations of people who don’t tire of recalling the heroics of their ancestors.

Our grandfather Sahukar Basvenappa spearheaded the anti-British rebellion. We do not know how they came about the idea of establishing their own government, but popular theory says ours was the first village in the nation to do so, says S. Shivayogaradhya, a second generation advocate from the Sahukar family.

His younger brother Basavaradhya also joins him in narrating the fateful incidents of August 1942.

It was the time when Gandhi’s Quit India movement had galvanised many rural level agitations. “The decision to appoint a ‘prati sarkaar’ was taken during a village gathering at the Veerabhadraswamy temple premises in the early days of August. The tricolour was hoisted and my grandfather announced that they would refuse to pay taxes to the British government,” explains S. Basavaradhya.

Sixteen-year-old Jayanna from the Sahukar family and Malapayya from the Gowdar clan were appointed the Tehsildar and sub-inspector of the newly formed provisional government respectively. “My great grandfather knew well that minors could not be jailed or killed. Hence he appointed under-aged boys to run the village government under his guidance. Sahukar Basavenappa and his comrades even wrote their own rules and regulations,” recounts Sahukar Basavaradhya.

Read More:

Freedom, at what cost? Jawans and martyrs' families speak up

How the British East India Company managed to colonise India for nearly 200 years

‘He went mad after he woke up’- experiences of black terror in Andaman’s ‘Kala Pani’ jail

This was soon followed by villagers insulting revenue officers who visited Issur to collect routine taxes to the British government. “Not only did they disobey them, but even snatched and destroyed important revenue documents,” says Shivayogaradhya. A complaint lodged against refusal to pay taxes irked the British government who sent in a team to check on the situation.

Issur is no ordinary village. Hot headed behaviour runs in its people’s genes,” begins Kausalya Bai, the daughter-in-law of Mr. Hucharayappa, the last surviving witness who partook in the 1942 rebellion. “Bold letterings on a black sari at the entrance of the village literally banned ‘English dogs’ (British representatives) from entering the village. It even warned of fines and punishments for those who dared, she further adds.

The same board greeted the team of Tehsildar Chennakrishnaiah, Sub-inspector Kenchegowda and eight other policemen who were given the responsibility to pacify the agitators.

“A crowd assembled at the open field near the temple again. This time the villagers forced the Tehsildar and Sub-inspector to wear Gandhi caps. Threatened by the heated atmosphere that had started to build up, Kenchegowda fired a few shots in the air. However, it only worsened the situation which ended up in the lynching of both officers,” Basavaradhya elaborates.

News about the firing spread like wildfire. Women and children of all ages ran to the temple area armed with sickles and logs of stocked up firewood. “Yes, they had beaten them to death with just wooden logs. Such was their anger and vengeance against the British, whom they went around calling red-headed monkeys,” narrates Kausalya Bai, who also makes up for the absence of her freedom fighter father-in-law. N.S. Hucharayappa served five years in prison for actively participating in the rebellion.

She further explains how Kadappagowdar from the nearby Choorchgundi village then transported the dead bodies to Shikaripur in a bullock cart. The sight of the brutally bruised corpses served like the last nail in the coffin for British top guns who were infuriated by the act of Issur’s rebels. “Warnings of armies marching in started doing the rounds. My grandmother and her friends were scared that there would be more “benke malle” (bloodied rains meaning gun fires).

They lowered their valuables and belongings into wells and hid in nearby jungles. Grown up men started fleeing their homes fearing arrest,” she adds.

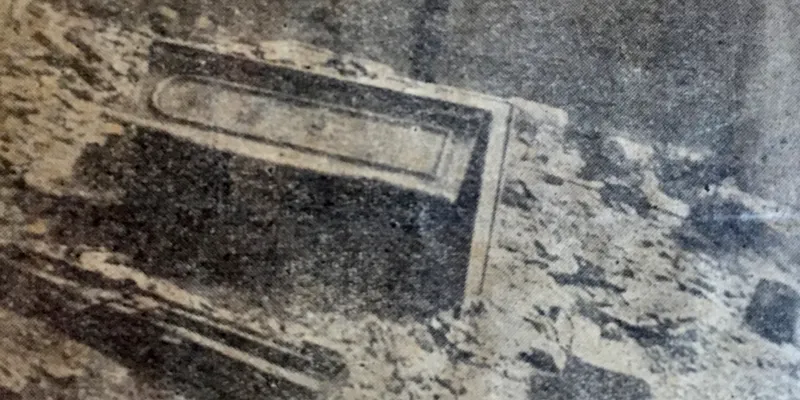

It was almost four days after the lynching of Tehsildar Chennakrishnaiah and Sub-inspector Kenchegowda that the army marched into desolated Issur. Basavaradhya shows me pictures of an age-old article that first published pictures of their burnt down house. According to reports, key witnesses and passed over narratives, the British armies that raided Issur indulged in indiscriminate looting, arson and even inflicted unreported atrocities against women.

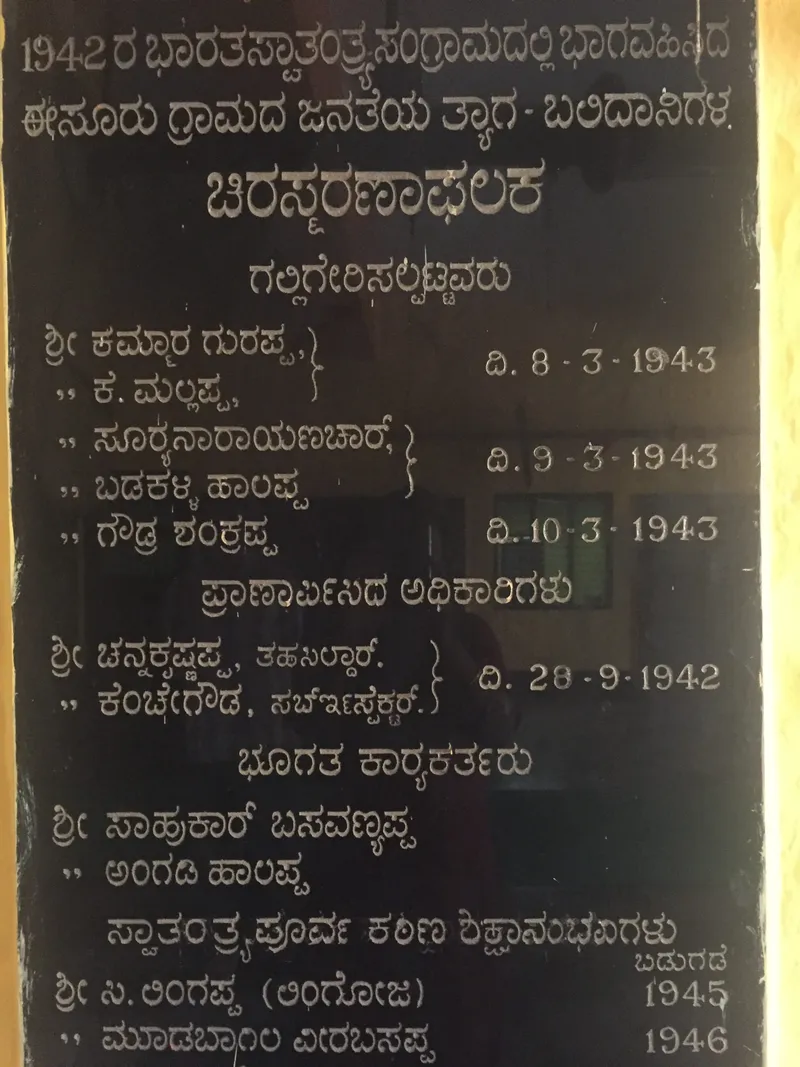

Several arrests, court hearings and sentencing followed those dark days that had scarred Issur’s august skies forever. A black stone engraving which honours the sacrifice of several villagers who were handed death penalties and life terms stands in the renovated temple courtyard today. It also lists the names of three women who were sentenced with rigourous life imprisonment.

“Esuru kottaru Issuru kodevu” (We’ll give you many villages but not Issur) was the phrase that then Mysore Maharaja Jayachamaraja Wodeyer coined to immortalise Issur’s bold anti-British uprising. Basavaradhya explained how the Wodeyer king even played a pivotal role in convincing the governor to commute the sentences of many people who were sentenced with the death penalty.

However, five mutineers namely Gurappa, Malappa, Suryanarayanachar, Halappa and Shankarappa paid the ultimate price when they were hanged for the double murders of Issur in March, 1943. Their names and details exist till date, alongside a concise report by British officer A Henry in the Village Crime History records at the Shikaripur police station.

Our grandfather was fortunate enough to be never caught. The British could not reach him as he was hiding at the ‘Kavaledurga mutta’ (religious congregation). He did not budge to surrender until his last days, Basavaradhya concludes with an amiable smile.

The wheels of time have turned and this year the Indian government proudly commemorated 75 years of the Quit India movement. However, small rebellions like that of Issur which fought the British valiantly remain buried in the sands of time, even as they are seared into the memories of a few who pass on the legacy.

Enter the SocialStory Photography contest and show us how people are changing the world! Win prize money worth Rs 1 lakh and more. Click here for details!