Finding the Silicon Valley of the East: China

Who will lead the next technological change?

Ten years ago, people undoubtedly trained their eyes on Silicon Valley garages for an answer. But now, seeing the rapid growth of aspiring competitors in the East, even tech savvy observers may request more time to give it a thought. China, India, and Southeast Asia have all shown their great ambition as well as fast growing competence in the tech industry. Each of them enjoys a large population with numerous emerging needs in internet business. At the same time, they also represent the most significant target markets for each other.

China shows great attraction as a prosperous market and also as a rich mine of thought, experience, and capital. Its high mobile internet penetration along with a tech-savvy user pool save entrepreneurs’ efforts to educate the market. Its well-established IT infrastructure and active venture capital market also contribute to a favorable environment for tech startups.

However, in this market, we see strong global competitors in most cases, leading players in the world – retreat from the battle against their local counterparts. The most recent and significant case might be Uber China’s epic merger with Didi. On top of the list, we can also find a few other well-known names such Yahoo and Ebay, among others.

Does this imply that China is still a long way from creating an ideal tech hub for global payers? We interviewed representatives of each different stakeholder group to hear their opinion.

Information transparency: a systematic problem

Mettl, an Indian SaaS startup operating in 80 and more countries, tried to enter the Chinese market. However, at the moment, it is yet to see substantial progress.

“The biggest challenge during our current attempt to enter China has been inadequate knowledge of the market,” commented a Mettl employee in an email interview with China Tech Insights.

The interviewee stated the following reasons that may have ushered in the current situation:

- Due to the language barrier, it has been very difficult for startups to do research, competitive analysis, etc. about any company/sector at an acceptable cost.

- Quite a number of tools which Indian entrepreneurs thought were a default choice don’t work in China. For example, “Linkedin in China has only half the number of users of India”, which makes it harder to connect with the right person.

- Since English isn’t the official language in China, it can be challenging to find available and clear English translation even for administrative documents or procedures.

“We had to talk to at least seven-eight Chinese consultants to get a clear idea of what the requirements for an ICP license are,” said the interviewee.

Dealing with the language barrier is just the first step. Apart from that, the differences in legal systems can be an even bigger headache. In China, where it requires immediacies in law establishments to regulate the market, the government may release sets of regulations, statutes, and guidelines for immediate use. This is also often the case in a fast changing business sector, such as the tech industry.

“Most startups are in the internet business. The past two years witnessed a burst of new statutes, regulations, and rules intensively aimed at regulating the internet sector,” a Chinese lawyer familiar with the scene commented. “And in some areas, there can also be detailed rules for execution at the municipal level, which startups also need to comply with.”

Regulations launched last November for ride-hailing services in China can be an example. After national regulations for ride-hailing services was launched, municipal governments in Beijing and Shanghai each released their own stricter rules that required local household register and local car plates for drivers to limit the numbers of cars on the road, considering the population and congestion in these two mega cities.

“And sometimes, these rules and regulations can be ambiguous,” such as the regulations for live streaming business in China. “It leaves space for development for emerging sectors. But at the same time, there is also the risk that administrators may impose more restraints and tighten the regulation when it's considered necessary. This kind of sudden changes in the regulatory climate may take away the chances for business in emerging sectors. Thus this also appears as a sort of uncertainty for startups in daily operations,” said the lawyer.

As for global startups, it first takes much effort to find trust-worthy agents to familiarise startups with the scene; then they also need time to learn to adjust to such a fast changing regulatory environment while navigating through all these uncertainties.

Want a Mr Clutch? Not an easy thing

What’s also noteworthy is that in some instances, through the right person is hired, the previously mentioned issues do not cause too much trouble. A skilled lawyer or an excellent government relations coordinator can help the company earn a lot more leverage in critical issues. However, hiring such a Ms or Mr Clutch isn’t an easy thing.

Although the degree of exclusiveness in China’s tech industry is not as severe as the notorious Silicon Valley scene, it is still hard for expats to connect to the right person. In many cases, a degree from a top university, or a stunning working experience in BAT or other top tech companies, can be the required ticket for entry to the right social “circles” in China. These circles normally include the best investors as well as outstanding entrepreneurs. When it comes to the right circle, term sheets and contracts can be signed in minutes.

In addition, considering the great cultural conflicts between headquarters and the local team, it is always challenging to find an appropriate candidate to be the cushion between the two. “Building up Chinese leadership has been an issue for MNCs even since Yahoo entered China in 1998,” said Hans Tung, partner at GGV Capital.

“Foreign leadership is normally alien to the Chinese market while headquarters normally would not be comfortable with a too-localised Chinese CEO. This contradiction has led to a lot of problems.” Uber China, as an example, was not able to see the assignment of its CEO to the local company even when it merged with its competitor Didi.

However, good news for some global startups is that as the Chinese tech industry prospers, there appears to be a reverse brain-drain – many Chinese tech practitioners who have worked in celebrated global tech companies are willing to return to the Chinese market to meet new challenges, such as Qi Lu, the current president of Baidu, and Hong Ge of Airbnb.

It took Airbnb three years to finally come to the decision of nominating Ge as the head of its China operation. He seems to have the qualities that fit both the need of a global team and a local market.

“Ge is a great choice. He’s a Yale graduate with a good performance in product development at Facebook. So he’s able to communicate well with the overseas team, fit into the company culture, and at the same time, he has a good understanding of the Chinese market,” commented Tung. GGV is an early investor of Airbnb. “And based on our communication with the headquarters of Airbnb, we see strong trust in Ge.”

“Also because of his experience of product development at Facebook, he’s trusted with a stronger say in product decisions. This, to an extent, eases the problem that local teams didn’t have enough decision making power in product localisation as it happened before to global tech companies upon their entry to China.” Tung said.

In many cases, investor recommendations are a key source for global startups to hire the right person. Flitto, for example, is a global translation community incubated in London. When it entered China, it decided to build up a local team starting with a local responsible person. Henry Huang was a product manager at Baidu and previously at Weibo, and was one of the candidates recommended to the Flitto team by one of their investors. He is now the company’s China president who built its Chinese branch from scratch, and now leads the company’s partnership with top Chinese tech companies including NetEase and his previous employers Baidu and Weibo.

Another challenge for startups concerning this long and tiring hiring process is that, even if you are fortunate enough to find the right person, chances are you will find the cost to be quite a burden. In the past few years, the labor cost in China has risen significantly. People’s Daily reported in 2016 that from 2013 to 2016, “the percentage of labor cost in a company’s overall cost rose from 5.8 percent to 9.17 percent.”

In the tech industry, a good offer can be more financially demanding for companies. And for startups, even a lucrative package isn’t enough to attract a wanted talent. “It’s common that someone you consider suitable won’t be willing to join your team, and wants to join a big company like BAT,” said Henry Huang, the president of Flitto China. “Cost isn’t the biggest problem. For startups, it’s even harder for you to meet and then be able to hire the right person.”

Before you’re ready to come in, they are ready to go out

Another challenge faced by foreign startups is how to adjust to the fast pace and fierce culture of entrepreneurship in this market.

“Chinese companies scale a lot faster than companies in India. The tremendous pace at which companies grow is a striking feature of the Chinese startup ecosystem,” said DhanasreeMolugu, analyst from Blume VC, in a comparison of the distinctive features of the two markets. “Besides, we also find a greater sense of discipline and hunger in Chinese entrepreneurs.”

This sense of hunger shared by Chinese entrepreneurs can be reflected by slogans like “996,” which means “working from 9 am to 9 pm, and six days a week.” In this swiftly changing market, no one dares delay one iteration or two of essential features compared with their rivals. In exchange, they are willing to sacrifice leisure and even health. These sacrifices are, somehow sadly, the foundations of the achievements of Chinese tech companies today, and to a certain extent, one of their core competence that stops outsiders to easily gain any market shares in this market.

“In China, there have already been pretty competent local players,” said Tung from GGV Capital. “They’re not only competent in the domestic market. They’re even ready to expand to the global market. With such competitors at home, of course it’ll be even more demanding for MNCs to enter the Chinese market.”

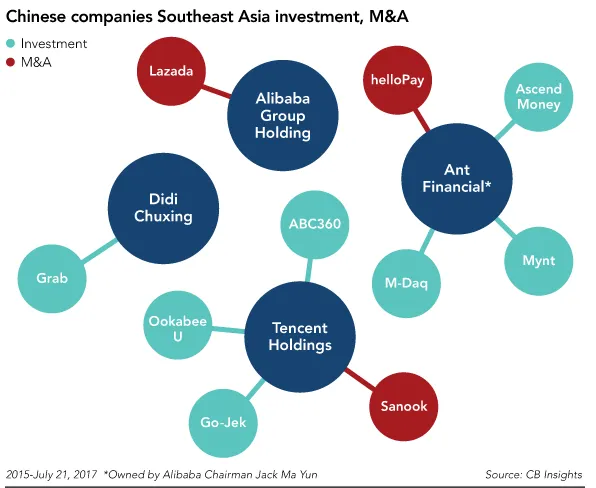

According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, in the first half of 2017, Chinese investors have made outgoing non-financial direct investment to over 145 countries and 3,957 companies with a total number around $48.19 billion. Despite a sharp year-over-year decrease of 42.9 percent in total volume, Chinese investors have become more active in the Asian markets. According to CB Insights, since the end of 2015, Chinese tech companies have invested at least $3.27 billion in Southeast Asian startups.

Top companies such as Alibaba and Tencent have made vast investments in companies related to their core businesses, such as Alibaba’s investments in Lazada for its e-commerce business, then Ascend Money and Mynt, in alignment with its online financial services. Apart from financial support, entrepreneurs also value the experiences brought to them by Chinese investors.

“Chinese investors have witnessed the fastest growth of any economy in their country. They have first-hand experience of scaling in a short time and yet creating a strong business. This learning is rare and is of great value to startups in India,” concluded the founders of MechMocha, an Indian gaming company with investments from Shunwei Capital, the venture fund founded by Xiaomi’s founder Lei Jun, when asked about their observations on the most distinctive features of Chinese investors.

Back to the question at the very beginning: is China ready to be the center of the Asian tech market and have its own Silicon Valley? Based on her observation of the Chinese market, DhanasreeMolugu from Blume VC gave her answer as an outsider. “We believe that a lot of cultural factors, such as globalisation and a reverse brain drain, and structural changes, like the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative and the ongoing economic reform, are shaping China’s path ahead in the tech world as a leader.

“The Chinese tech industry has the unique advantage of having a strong manufacturing base which supplements the software and consumer internet businesses really well. Another factor favoring China is the depth of the venture capital industry. It can be regarded as the most advanced in Asia in terms of experience and scale compared to others, including India’s nascent VC ecosystem.

“We also observe that the Product Managers of Chinese consumer tech startups have a very keen insight into the customer's psyche and deliver a great user experience. All these factors definitely make China a strong contender for the title of ‘The Silicon Valley of Asia’.”

“However, after spending a few weeks in China meeting investors, startups, entrepreneurs, and college students, we realise that the focus on localisation of Chinese startups is relatively high, and the government support for local business is pretty strong, which limits the scope of global companies to enter China. Also, having seen a few of our portfolios struggle to tap into the Chinese market, we think the regulatory and legal aspect of doing business in China for international startups still is very hazy. A more expat-friendly environment in terms of information availability, communication efficiency, and many other aspects, is still needed before China can finally claim the title.”

Although China is yet to be a perfect destination for global entrepreneurs, we have already seen impressive stories happen every day. RazGalor is a 23-year-old Israeli content creator who speaks fluent Chinese and is currently a junior student at Peking University. He was a guest host of a Chinese reality show featuring young people from various countries who can speak fluent Chinese, introducing cultural differences of different regions, and he is now a content producer and entrepreneur. His online video channel Foreigner Study Association has 1.54 million followers on Weibo, and each of his videos has millions of views on Chinese social media. This is one of many successful expat entrepreneur stories in China.

According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, from January 2015 to May 2017, 66,634 new wholly foreign owned enterprises have been set up in China. And hopefully, with a steadily rising tech industry and a more open attitude, we may be able to see a more international, intercultural, and vigorous Chinese tech market.

In this series, China Tech Insights and Blume VC navigate through Asian markets to discuss the potential of entrepreneurship and globalisation in these markets, as well as challenges they are currently facing.

This article first appeared here.

This article co-authored by Dhanasree Molugu, Investment Analyst, Blume Ventures (India) and Rhea Liu, Analyst at China Tech Insights (China).