In search of a lost culture, this Singaporean man travelled to India

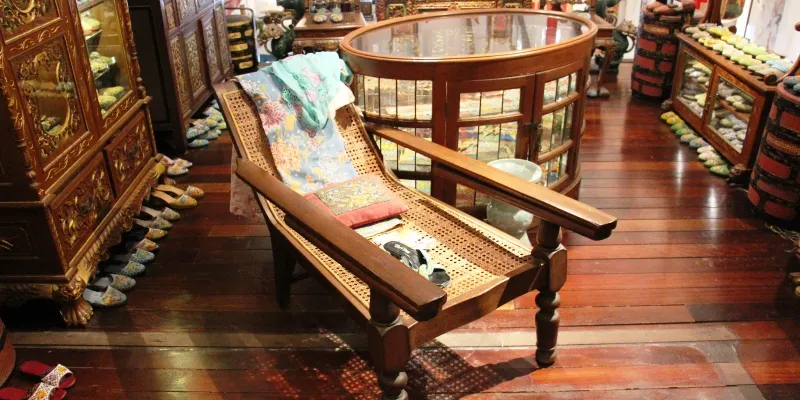

Due to the absence of a recorded history of his Chinese Peranakan culture, for the past 30 years, Alvin has travelled across Asia, including India, in search of his material and oral culture.

Alvin Yapp (47), from Singapore, visited India in search of his cultural roots. He says,

I have been collecting antiques for the last 30 years because as a young child I didn't know about my own culture. This is contrary to the Indian culture; In India, you would teach a child about his heritage and culture from a very young age.

After Independence in 1965, Singapore was geared towards economy building rather than chronicling the cultural past of its communities. Alvin belongs to the Chinese Peranakan lineage. As a descendant of Chinese immigrants who married native Malay women, he always felt a sense of loss and ambiguity towards his cultural history and identity. For political reasons, Peranakans today are grouped as one racial group with the Chinese in Singapore, where the community has become more adoptive of the mainland Chinese culture, rather than maintaining their interracial roots.

Artefacts inscribed with Indian languages

His quest for cultural identification brought Alvin to India in 2002 where he discovered lost artefacts, enamel tiffins and spittoons, widely distributed across the country.

These objects of material culture — pieces which were made in eastern Europe, in Czechoslovakia and Poland— were purchased by the Indian traders and sent back to India as dowry, says Alvin.

In the last five years, many of these pieces have found their way back to Alvin’s independent in-house museum, The Intan, through the Indian runners he is connected with. These antique runners are spread across the Indian subcontinent, and are connected with two main runners in Chennai who supply and sell the pieces to Alvin.

“When we look at these enamel pieces we see Hindi and Tamil names inscribed; we can still see the initials on the spittoons and the tiffins.”

The Indian connection

Since both India and Singapore were former colonies of the British East India Company, the indigenous furniture, jewellery and even pottery had both English and local influences. When immigrants, largely from Tamil Nadu, travelled to the South-East Asia in the 1900s in search of better livelihood as traders, many Indian artefacts became a part of the culture of Singapore.

This community is today known as the Chitty Melaka, the Indian Peranakans. While retaining their Indian customs and practices, they married the native Malay women and adopted the Malaysian language, food, and dress.

The sarong that the Peranakans used to wear were made of Indian cotton, and the batik design had Indian influence as well, Alvin explains.

Quest for identity

The Chinese Peranakan community, to which Alvin belongs, was formed in the 1990s. It always focussed on earning a livelihood and has no recorded history. The culture of this community has now started to disappear in Singapore. Singapore classifies the Peranakans as ethnically Chinese, so they receive formal instruction in Mandarin Chinese as a second language, in accordance with the "Mother Tongue Policy” instead of Malay. Hence, Baba Malay, the creole language spoken by this community, was replaced by Mandarin and English.

At the tender age of seven, Alvin realised that he was different from his friends in terms of the language they spoke and the food they ate. While his family conversed in English, the other children in his school spoke Mandarin; further, the food they ate had Malaysian influences, with the heavy usage of Malay spices.

Our attitudes and behaviour was also different. I spoke English and grew are up watching Hollywood films unlike my Chinese friends who discussed Hong Kong films instead. Since then, I got curious about the Peranakan culture, my own culture.

As a teenager, he started going to the flea market, garage sales, and antique shops. Soon he started to collect not just the artefacts but also stories which the shopkeepers shared with him. As the collection grew, people started to visit him. In 2010, the National Heritage board of Singapore suddenly visited Alvin and asked him to became a member of the Museum Round Table Association.

The following year, The Intan, was awarded the ‘Best Museum Experience Award’ by the government.

Haven for culture

I own the pieces of the collection; I use my own money to sustain it. The museum visits helps us sustain the operation of the museum; which is essentially the cleaning, the utility, the manpower. But it is not enough to fund the purchase of an item for the museum.

Alvin also works in his 34-year-old family business, Busets, an outdoor printing company to earn his livelihood and continue purchasing new antiques.

Although he has sometimes been duped and sold fake items in the name Peranakan culture and heritage, he continues to remain undeterred.

He says, “I think it makes us a better person to know where we come from, who we are. To know our past is to know how we are here today; hence, it allows us to face the future. Being able to appreciate the culture and the lives of our forefathers makes us well-rounded individuals. It is important.”