Cerebral palsy got Prasanth Kamath rejected by schools, today he is a celebrated app developer

Prashanth exemplifies that disability is a mere limitation of the mind and with the right support and intent, truly, sky is the limit.

Forty-three-year-old Prasanth Kamath defies all stereotypes associated with cerebral palsy. With an infectious laughter he shares his life story — from being a school reject to a first-ranker of the state board exam. Against all odds, Prasanth not only completed his BCom but is now a celebrated mobile application developer.

Battling his ‘spastic’ condition, wherein his body experiences involuntary movements, Prashanth has managed to work full-time work with Mindtree for over a decade and is a part-time share investor.

Dr Ashwini Suri, Prasanth’s sister and caregiver, says,

He is someone for whom even 24 hours are less. He has a lot of plans. He has a brilliant mind with a ‘never give-up’ attitude. When he is awake he is very productive. There is no medicine or treatment for his condition. It is a motor disability.

Realising that a lot of other specially abled people behind closed doors need to be encouraged, Prashant tells us,

This is not about me. At least somebody should get inspired. Don’t limit yourself.

Having a corporate job

Prashanth never knew what it means to be idle. His mission in life, as he tells me, is crystal clear.

I wanted to work instead of just sitting at home. I wanted to do something.

India already grapples with unemployment and despite the policies to increase sustainable livelihood opportunities for persons with disability, corporates are reluctant to offer jobs to this community.

Prashanth’s family, aware of his desire to work, reached out to the Spastic Society of Karnataka for help, who in turn connected him to Mindtree. The society had designed the Mindtree logo, therefore getting the job was the easy part.

However, finding an appropriate role for Prasanth was difficult. Ashwini (40) recalls, “It was not about the lack of money or intent on their part; they just dint know which job profile would suit him.”

Prashanth tells us,

When I joined Mindtree they couldn’t figure out where to put me. I was put in HR but I did not like it too much. Even now I like doing technical work. For about two years, I continued with HR, and then I got a chance to work with Subroto Bagchi. I proof read one of his books.

Prashanth was always eager to learn and develop his skills in computer and IT. His zest for knowledge and his eagerness to help the larger specially abled community, drove Mindtree to start a separate department for him in assistive technology.

There Prashanth became well versed in Java, .Net, Python and C++. Further, he also started to develop and patent mobile application, Typing Button — an assistive technology application for people which converts text to speech. While he gained recognition for his work, Prashanth believes there is still a long road ahead. He also realises that technology can be a positive force for inclusiveness.

Unless and until you have a problem you wouldn’t know what kind of trouble you have and the solutions you need.

Besides, Prashanth has also been instrumental in the famed ‘I Got Garbage’ project of Mindtree.

Quest for knowledge

Prashanth today has a steady job. However, this journey was far from easy. In the 1970s, the lack of awareness about the problems and the needs of the specially abled community posed a challenge for his family.

Prashanth was a premature baby, and due to a complication during his birth, the supply of oxygen to his brain was cut-off for more than four minutes. This caused cerebral palsy and Prashanth’s parents realised his medical condition only two year later.

I still remember we used to place pillows all around him, so that he wouldn’t hurt his head by falling off, remembers Ashwini.

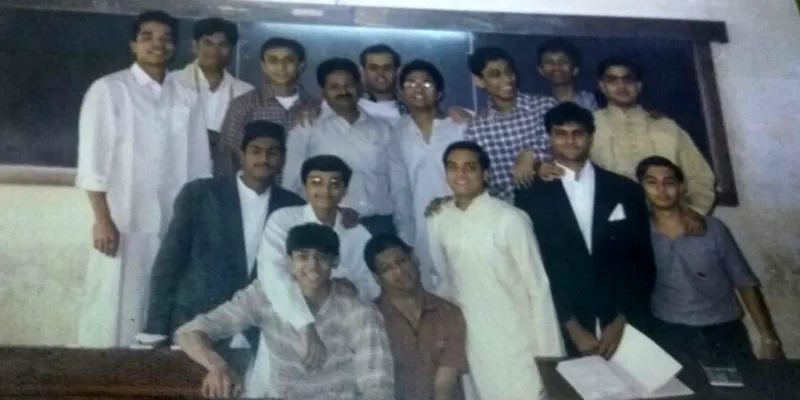

Due to the lack of institutions for motor disabled people, Prashanth was initially forced enroll in Hamsadhwani and Shree Ramana Maharishi Academy for the Blind. Later he joined the Spastic Society of Karnataka and became a part of their first batch for the tenth board exams. Prasanth ended be securing the top rank in the state, but the school refused to help him with further education.

The three students were the first batch who completed tenth board exams at Spastic Society of Karnataka.A newspaper article, about a specially abled person who had passed his class 12 exam from Mumbai, provided hope to the family and they decided to shift to Maharashtra. Eventually, after a tempestuous pursuit of education, Prashanth was propelled towards the development of computer applications and training in the IT industry. Ashwini recalls,

His brain is very sharp. My mom literally carried him and took him all the way from Kurla and Ghatkopar to Chembur for his vocational training. She used to take a public transport every single day. Not once was he absent. And for three years he learnt computers.

Meanwhile after her class X board exams, Ashwini negotiated with the South Indian Education Society, Mumbai, to secure a seat for Prashanth’s further studies. However, the headmistress was sceptical, worried about “where he would sit in class?”

I said he would adjust somewhere. Just let him sit. We were not even particular that he should take the exams; we wanted him to gain some knowledge, we wanted to let him improve in life.

Prashanth not only completed his class 12 education but secured the first rank again in the exam results. He went on to finish his BCom with the rolling trophy of the ‘Best Student Award.’

I want to tell you that in first year I stood first — I got 97 percent in seven out of eight subjects. In the second year, I stood second and in my final year I came first again, Prashanth says as he beams with pride.

Fighting all odds with love

The years that followed were laced with a long wait for employment. Opportunities were scarce for the specially abled community in early 2000s. During this period, Prashanth started to trade in shares, as a part time hobby. And in a span of 10 years, he converted Rs 2 lakh to Rs 24 lakh.

During this entire period, Prashanth’s family stood as a rock and refused to indulge in negativity or ‘what ifs’. When I ask Ashwini about the years spent in taking care and providing for her sibling, she says,

The kind of love you get is just unconditional. Every relation on earth is sort of give and take. I don’t think any sibling would have had this bond if it wasn’t for a special child. Being with him is rewarding.

Prashanth exemplifies that disability is a mere limitation of mind and with the right support and intent, a specially abled person can confront the challenges and embark into a horizon of limitless possibilities.