Why Indian fintech failed to make the big leap in one year after cash ban

It is a year since demonetisation yet the Indian fintech seems to be servicing only the top 10 percent of the population. What’s stopping them to make inroads into Tier III and Tier IV geographies, and really take on a seemingly ready market for expansion?

It is 8:15 pm on November 8, 2016, and MobiKwik Co-founder Upasana Taku is at her dining table feeding her baby. At the other end of the room, husband and Co-founder Bipin Preet Singh is glued to his television screen awaiting Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s address to the nation – a typical scene in any Indian household.

What came of the address, however, was anything but typical for any and every household across the country.

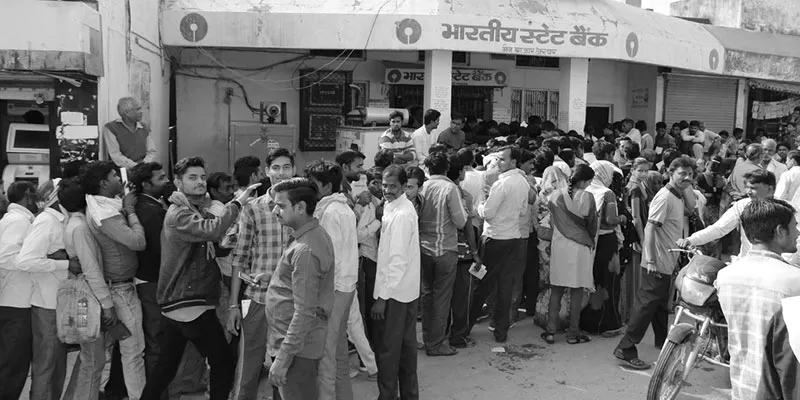

Modi declared high denomination notes would not be legal tender in a matter of less than four hours, sending shockwaves all across.

Overnight, around 86% of the currency in circulation was barely more than printed paper, but Bipin was elated. “Upasana! This will change everything,” were his first words, recalls Upasana.

What followed was a frenzy of phone calls from friends, family, teams across operations seeking directions, and journalists – all trying to make sense of what was happening.

This was a year ago, and a year hence, the Indian economy, as well as every sector that makes it up, is trying to decipher the effects of demonetisation and the future course. One sector that got pushed to the forefront as Rs 500 and Rs 1000 notes became invalid was digital payments and wallets.

Almost overnight, popular wallets such as Paytm and MobiKwik saw an over 100 percent rise in transaction volumes, with the later seeing three million daily transactions post demonetisation as against 1.5 million earlier, and Paytm recording seven million daily transactions as against three million transactions before demonetisation.

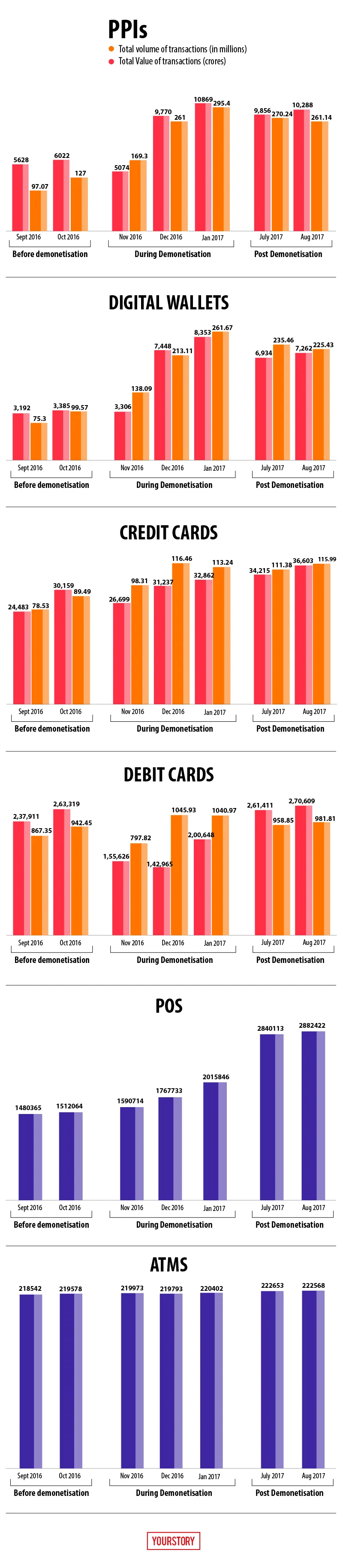

Banking and industry experts trained their sights on the space, all declaring fintech to be the next big thing in India. Digital payments saw a sharp spike in December 2016 taking the base up significantly and then plateaued as the year wore on.

In October, mobile wallets saw 100 million transactions, which jumped to 138 million in November, 213 million in December, and 261.6 million in January 2017. However, as the economy was remonetised, and cash again became the preferred mode of payment, transactions fell to 221 million in June, 235.4 million in July and 225.4 million in August.

Here's the graph which speks about the growth of payment instruments through demonetisation:

But, in September, online publication The Wire reported the government’s digital payments initiative BHIM, which runs on the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) had close to 20 million downloads. However, less than 30 percent of those who downloaded the app linked it with their bank accounts, engaging in active transactions.

Many, however, insist it is still early days yet, and things are waiting to unfold.

Manish Khera, who has over two decades of experience in the Indian banking system, and is the founder of one of India’s biggest correspondence networks, FINO Paytech, says,

“Our Indian fintech in general is one which is making existing banking systems more efficient, while expanding consumer segment. But, I am of the opinion that the expansion of the market segment might not really be happening.”

So, why is fintech not expanding the pie?

- Risky demographic and tying to existing banking models

Manish says,

“A vicious scale is always easier to demonstrate at the top of the pyramid rather than at the bottom.” And this scale is essential for Indian fintech players to show promise of fair returns to investors.

The top of the pyramid, says Manish, referring to the urban population, has the necessary infrastructure in terms of smartphones as well as soft skills to operate these phones and discover options. A paradigm which seems to be lacking with populations in Tier III and IV populations.

Currently operating the NBFC ArthImpact, which looks at providing SME loans to shopkeepers, traders, and semi-skilled workers in semi-urban areas, Manish says there are 800 million bank accounts in the country, but only 200 million credit bureau records.

Indian fintech companies essentially work with banks, and high-risk challenges do not align with the existing banking model. “Global experiences say that the income of a person (at the bottom of the pyramid) is uncertain and he is exposed to shock, manmade and natural disaster. Of course, you are running a risky model.”

- Revenue challenges

According to statistics, 50 percent of India’s workforce economy is agriculture-based. Manish says the formal banking system has recognised and reached the agricultural economy, but there hasn’t been much improvement in the non-farm ecosystem, referring to the small mom and pop stores, or kirana stores in Tier III and IV towns.

“The banking ecosystem is of the assumption that the non-farm economy in rural areas was way smaller. But in the last 10 years it has become equal or bigger to the agriculture economy,” remarks Manish. “While the government made a push to this segment, banks seem to have met only physical targets, giving out corporate loans. One good model was group lending, however it has stayed only with women,” adds Manish.

The average ticket size of a loan to a kirana store who earns Rs 10,000 can be Rs 30,000. While servicing the loan through installments, fund transfer systems (like NEFT, RTGS or IMPS) charge anywhere from Rs 5 (IMPS) to Rs 55 (NEFT), killing the scope of obtaining optimum margins while servicing these customers.

Understanding this in case of digital transactions, there is a hardware cost in terms of PoS devices. Of course, there is UPI and digital payment instruments, but the skill to use them continues to be low.

“You have to redefine processes. The cost structure doesn’t work. Incumbents run into viability of the business and model collapses,” adds Manish. Another point is the low penetration of incumbents in this space, which leads to less competition and thus innovation.

The solution?

“What I am expecting is that RBI will allow more PPIs to try banking on regime (as seen through Small Bank and Payment Bank licenses), which will drive more innovation from their end (leading to a wider net of inclusion),” adds Manish.

An industry leader, speaking on condition of anonymity, said,

“Giving a bank account is not financial inclusion. The rhetoric has been that bank accounts, through moves like Jan Dhan, is financial inclusion. It can be a part of it but not complete inclusion. Inclusion means access to financial services, solutions, bill payments, insurances, and basic micro-credit.”

Industry experts say the top 10 percent of India’s population is the easiest to reach and it is harder to penetrate below that 10 percent.

Another banking leader says,

“The whole ecosystem works on a command and control environment. Execution machines (like banks) have targets, saying x no of accounts, y no of loans and x portfolio of loan. Nobody is using the targets to grow the pie. And this is not letting banking and incumbents to go deeper.”

If payment companies also continue to focus on the top of the pyramid, the total digital transactions will continue to plateau, not yielding exceptional growth in transaction volumes.

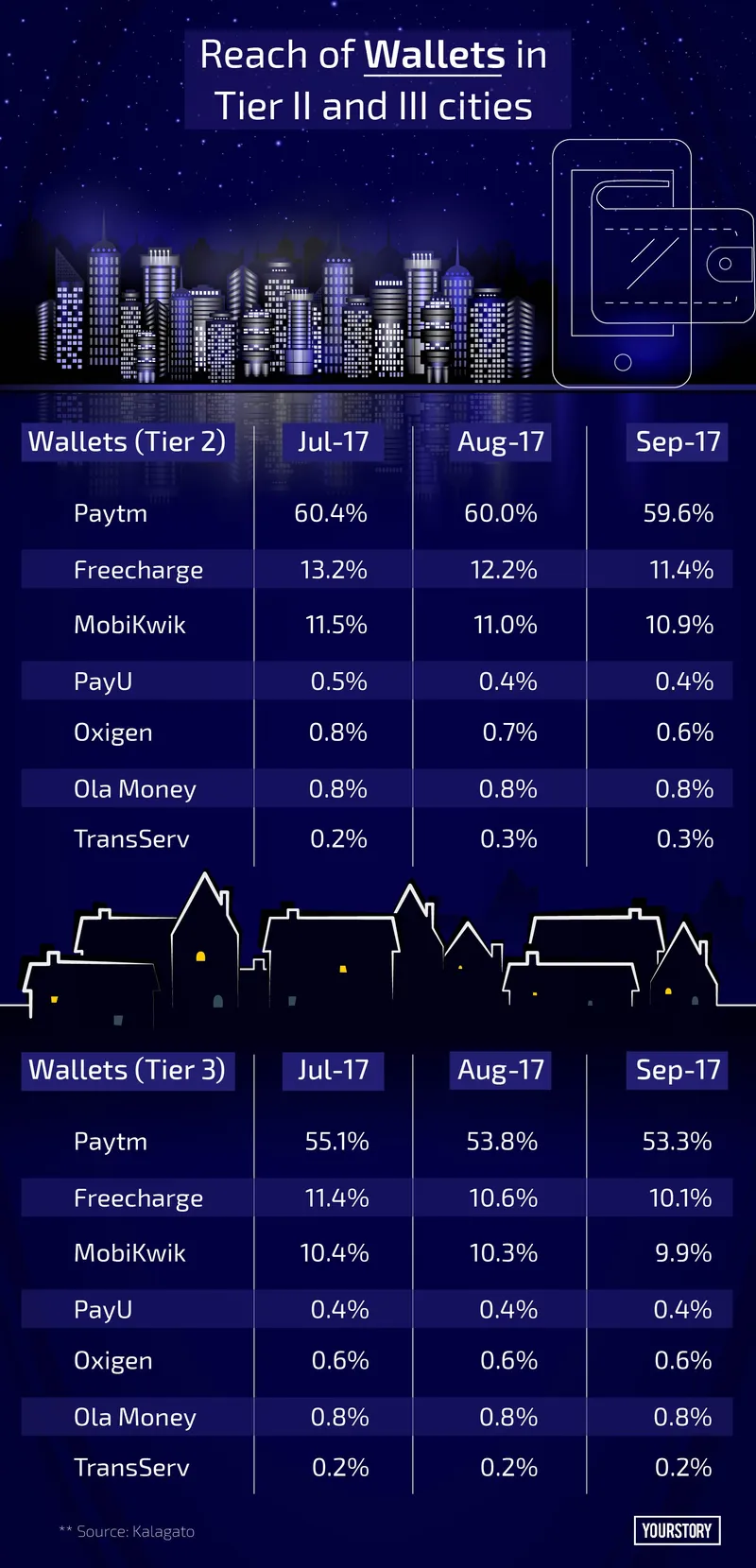

The below data from Kalagato talks about the major payment instruments and their penetration in Tier 2 and 3 towns:

An industry expert who didin’t want to be named, says,

“There is not much incentive to expand to Tier II cities. Yes, PPIs might have invested 60 percent in this category, which was reaching a new market. But now it’s going back to cash and we are again losing momentum.”

Light at the end of the tunnel

What Indian fintech companies are starting to understand is that is a huge opportunity in the semi-urban populations. A couple of answers, in fact, are in the Tarun Ramadorai Report of Household Finance Committee, released in August this year.

Highlighting some of the key behaviours of Indian households, the committee says Indian households associate formal banking with large administrative burdens and complicated paperwork. Further, with the participation rate of Indian households in financial assets well below the one observed in developed countries, the largest fraction of wealth is invested in durable goods and gold.

The recommendations of the committee could be some key areas of expansion for the Indian fintech sector. “Technological solutions hold significant promise for providing customisation and scalability simultaneously, and technological interfaces can help in depersonalising potentially embarrassing face-to-face interactions,” the report says.

Recommendations and scope for fintech sector include:

- Indian households require customised financial products that account for their unique economic conditions.

- Such customised financial products need to be scalable.

- These products need to be relevant to households, at a price that is fair, and dispensed alongside financial advice that is in the best interests of households.

- Complicated paperwork and bureaucratic impediments must be avoided.

The scenario now

In December, the Watal committee had suggested interoperability between banks and payment service providers to directly access payment systems. This was implemented in RBI’s master directions for issuance and operation of Prepaid Payment Instruments (PPI), encompassing digital wallets. The move was accompanied by another direction from the RBI around minimum KYC complaint wallets to be converted into full KYC compliant accounts within 12 months, or by October 2018 for existing wallets.

In a report, payment experts had told YourStory,

“These guys (at the bottom of the pyramid) are taken away from the formal economy. The low value transaction now gets costlier (for financial institutions) as there is a physical KYC cost, and a CAPEX cost if done digitally.”

Industry experts also suggest this move from the RBI will lead to merchants opting for one digital payment option instead of two or three, or in some scenarios giving away digital payment options completely because of the hassles of KYC.

Bala Parthasarathy, Co-founder of MoneyTap, had then said the cost of a single Aadhaar-based KYC can range between Rs 70 and Rs 300 depending on system efficiencies of payment players, and can run between Rs 100 and Rs 250 in the physical world.

This creates tension for new payment players and goes against the committee’s decision to “…safeguarding security of Digital Transactions and providing level playing to all stakeholders and new players who will enter this new transaction space.”

So, what did demonetisation really achieve?

There is one thing which one cannot deny was the real impact of demonetisation. As Bhavik Vasa, Chief Growth Officer, EbixCash says,

“Demonetisation won half the battle which lay in the mind shift of the consumer. Today, kirana stores are carrying one more digital instrument, and they want to be ready and have it as an option. And now transactions will follow. At least the option is ready.”

He adds, that a lot of work still needs to be done. “We need be able to get alternatives as simplified as possible and a majority of the work is happening now. The part which demonetisation has made easier is that the consumer is ready to listen. Because first, they listen, then trial starts and only then we see the scale. And the ecosystem is still at the trial base.”

As the industry marches forward, frictionless trial base rather incentive-based trials will become easier, and will be a lasting adoption for Indian fintech.

(For more stories on demonetisation visit here)