When corporates benefit from money meant for India's farmers

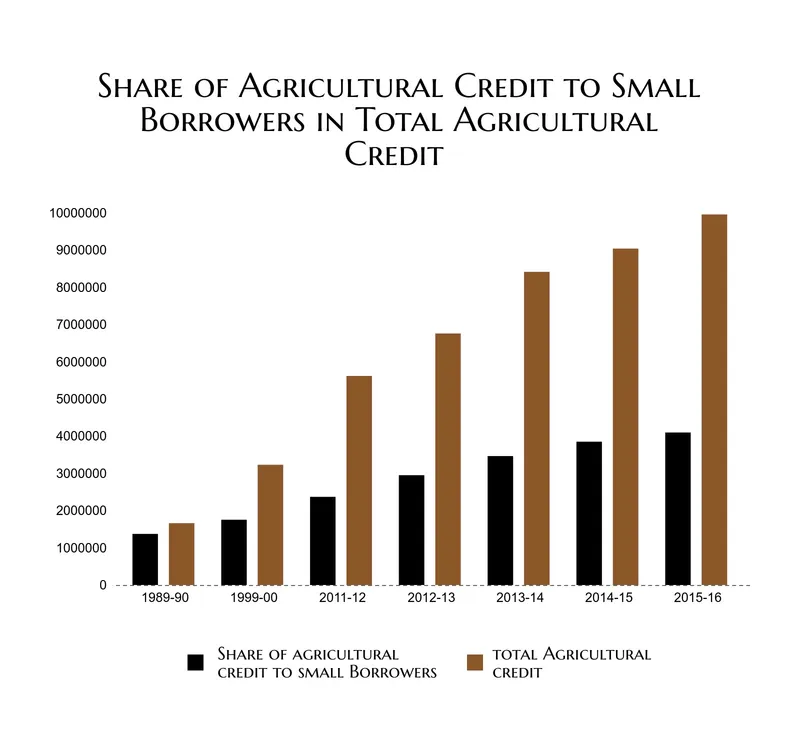

Credit to small and marginal farmers formed 82 percent of total agricultural credit in 1990. Today, the number stands at a mere 41 percent.

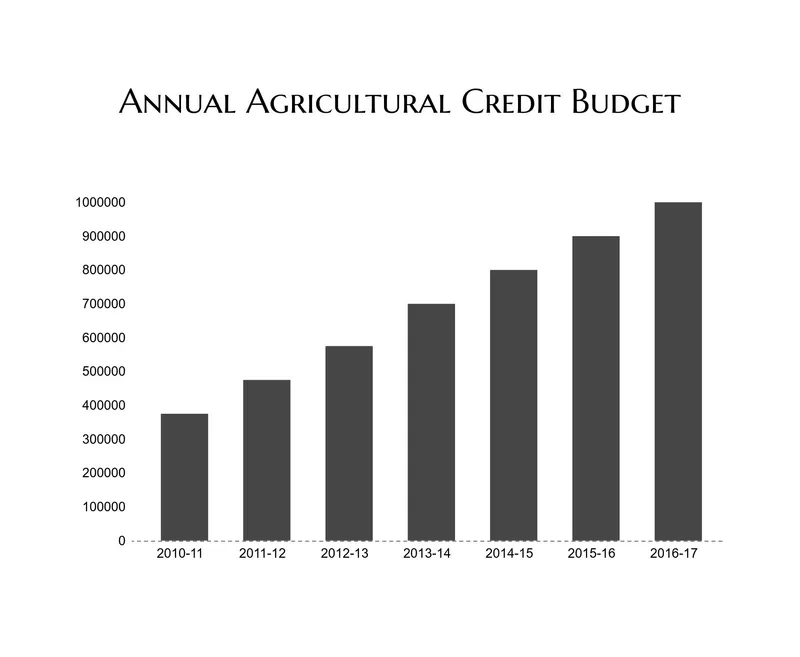

When the Centre announced its budget of 10 lakh crore rupees for agricultural credit in January 2017, it was hailed as a ‘major thrust’ and a ‘bonanza’ for farmers. But going by the trends in the supply of agricultural credit over the past 10 years, it seems unlikely that this record budget has had any tangible impact on the productivity of small and marginal farmers.

After a sharp decline in the decade of economic reforms, the annual growth rate of agricultural credit began its recovery in 2005.

Between 2004-05 and 2014-15, it grew at a compounded annual rate of 24 percent. The Ministry of Agriculture in its ‘State of Indian Agriculture (2014-15)’ report proudly mentions that institutional credit supply to agriculture not only met annual targets in these years but consistently surpassed them.

Yet, 85 percent of marginal farmers and 45 percent of small farmers remain outside its reach. Who then has been profiting from these credit bonanzas every year?

In a study titled ‘Bank Credit to Agriculture in India in the 2000s: Dissecting the Revival,’ Prof R Ramakumar and Dr. Pallavi Chavan find – “the major beneficiaries of the revival in agricultural credit in the 2000s were corporate groups and other organisations indirectly involved in agricultural production, and not farmers who were direct producers in agriculture.”

Their study presents the trends in the flow of agricultural credit between 2000 to 2011 but an analysis of the data over the past five years shows that their findings are applicable even today and that the exclusion of small farmers continues just the same.

How much agricultural credit actually reaches small and marginal farmers?

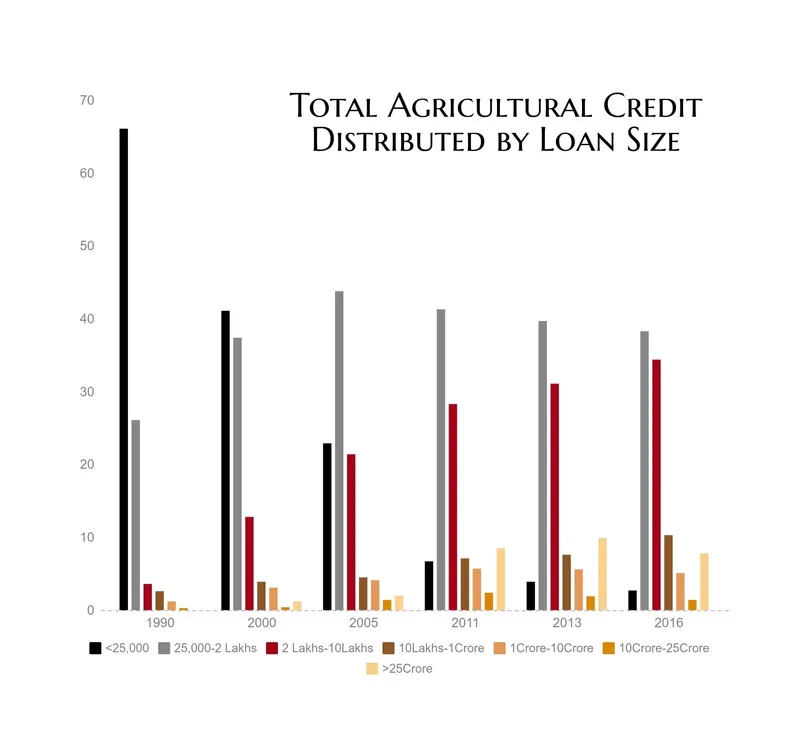

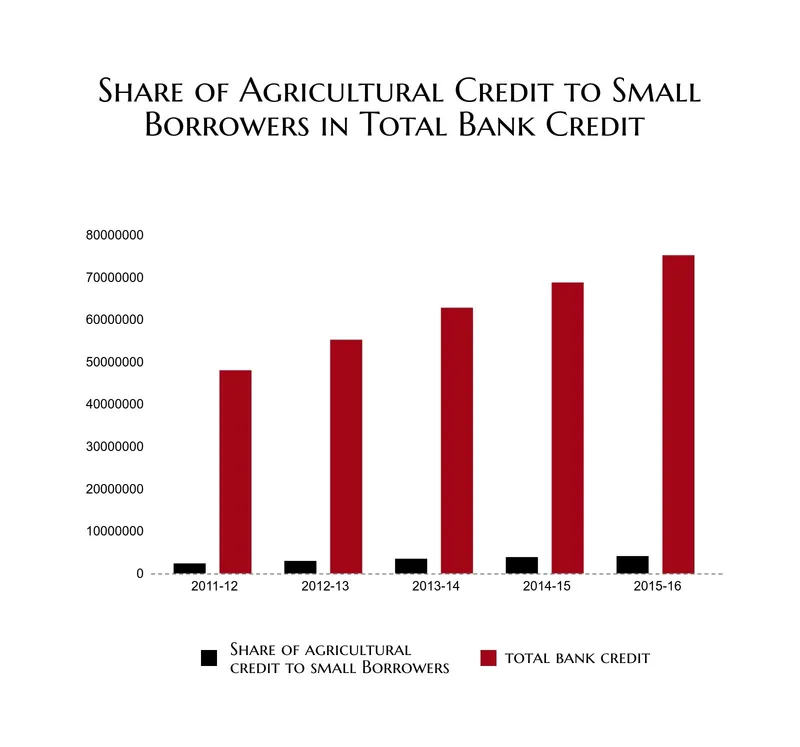

Farm loans of the size two lakh rupees or less are generally considered as agricultural credit to small and marginal farmers. In 1990, the share of these loans in total agricultural credit was 82 percent. Today, the number stands at a mere 41 percent.

Corresponding to this steep decline is a marked increase in large loans of the size no poor Indian farmer could afford. As the chart below shows, the share of loans between 2 lakhs and one crore rupees has steadily risen over the years, while the share of loans less than 25,000 rupees fell drastically from 1990.

Basic Statistical Returns of Scheduled Commercial Banks, various issues.

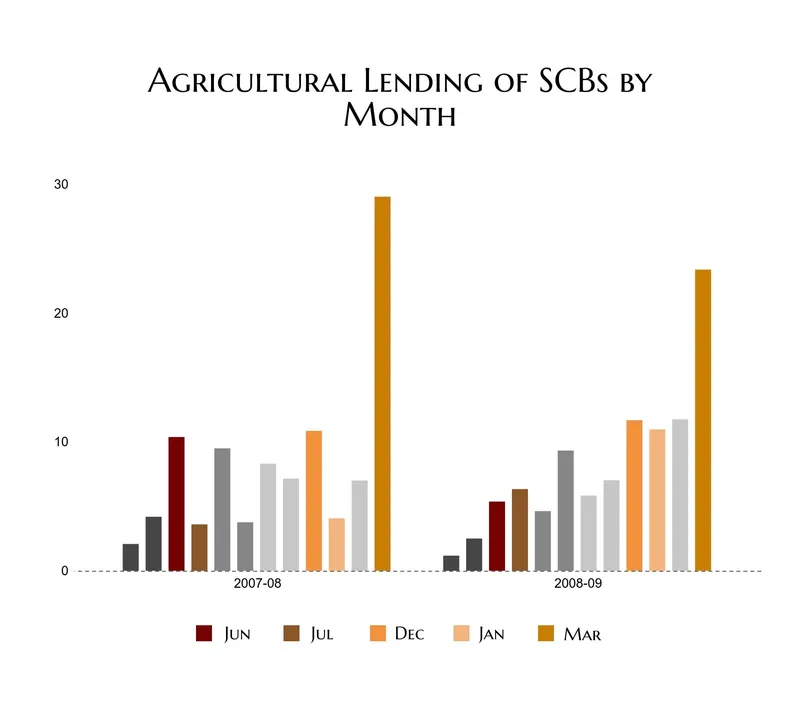

Another curious pattern in agricultural lending of commercial banks is the months in which its concentrated. The Report of the Task Force on Credit-Related Issues of Farmers (2010) revealed that 29 percent of agricultural credit in 2007-08 and 23 percent in 2008-09 were disbursed in the March, a month when credit requirement for agricultural production is not at its peak. In fact, the months when cultivators have the highest need for credit are June and July for the Kharif season and December and January for Rabi. The task force suggests that the disproportionately high disbursements in March could be due to banks giving out large loans to corporate institutions in that month and/or window-dressing by them to meet credit targets prescribed by the RBI.

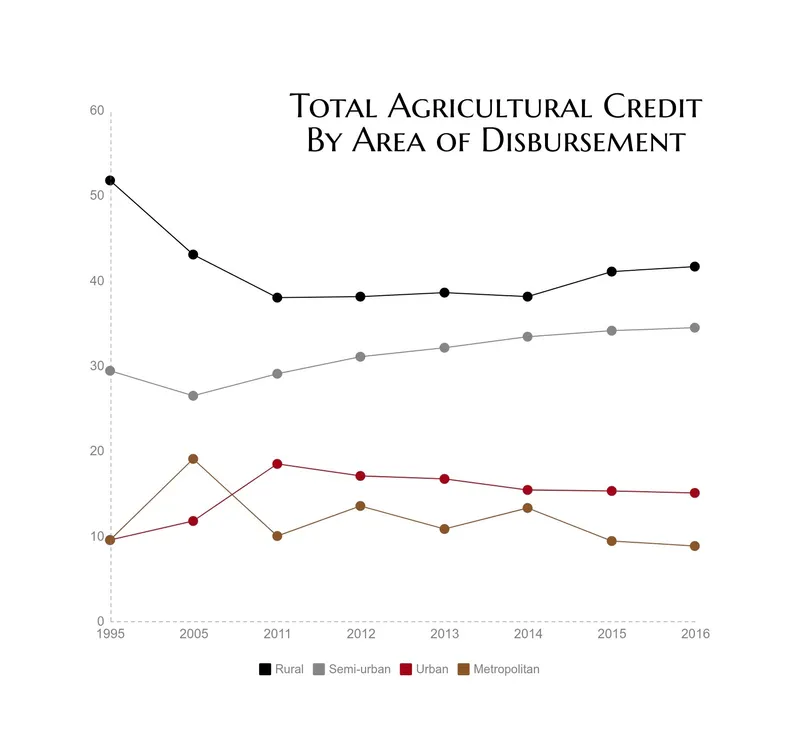

The geographical spread of these loans has undergone changes as well with a substantial portion of them now being disbursed in urban areas. In 2016-17, 26.7 percent of the total agricultural credit was extended by urban and metropolitan banks, no doubt to the scores of poor farmers working on the innumerable farmlands of Mumbai or Delhi.

Basic Statistical Returns of Scheduled Commercial Banks, various issues

Why has credit to small and marginal farmers declined?

Lending to small and marginal farmers is a risk most commercial banks are reluctant to take. If a portion of institutional credit still reaches these farmers, it is because of priority sector lending (PSL) rules which require banks to direct 18 percent of their annual lending towards agriculture. But successive governments, instead of tightening regulations to protect the economic interests of poor farmers, made it easier for banks to meet PSL targets without lending much to them.

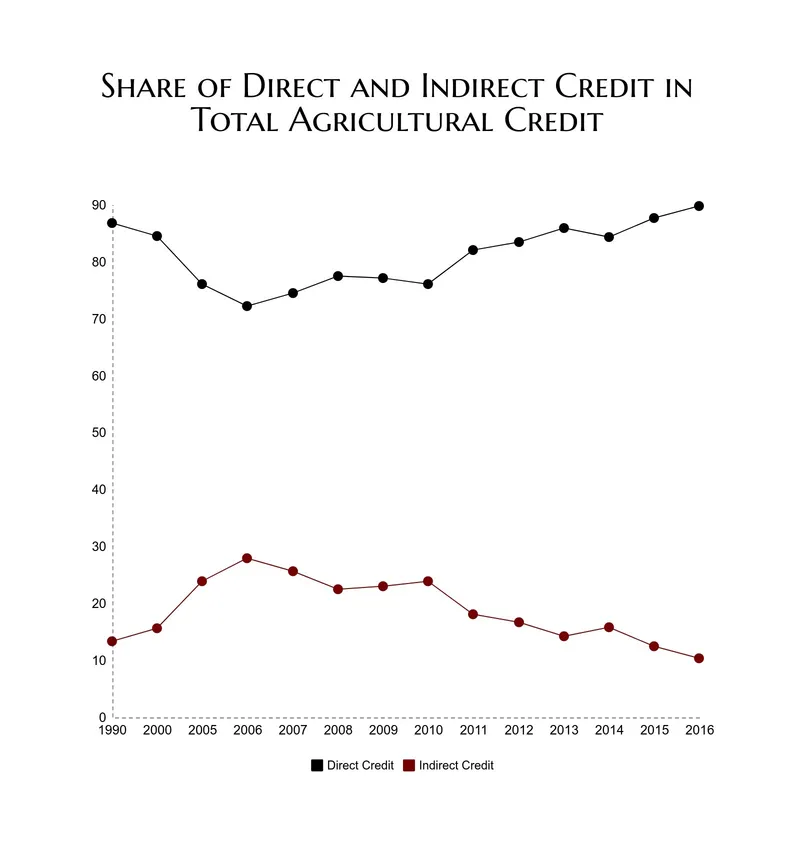

Agricultural credit is of two types – direct and indirect. Initially, the former included short-term credit to farmers for meeting seasonal input requirements and long-term credit for investments in irrigation and farm machinery. The latter meant credit to individuals or entities indirectly involved in agricultural production in rural areas such as input dealers or electricity boards. Post-reforms, however, these definitions began to expand.

For example, indirect credit came to include loans to agricultural machinery and drip-irrigation systems dealers and storage facilities constructors in both rural and urban areas, non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) such as microfinance institutions for agricultural lending, food and agriculture based processing units with investments up to 10 crore rupees, as well as loans greater than two crore rupees to agricultural corporations. By the RBI’s own categorisation, majority of these loans should fall under industrial credit, but it sees fit to make exceptions if they’re related to agriculture and allied activities.

The extent to which the meaning of direct credit has been diluted is even more shocking. From 2007, all loans to corporates, institutions and partnership firms up to one crore rupees and one-third of such loans greater than one crore rupees began to be considered as direct credit. This could explain why the share of direct credit in total agricultural credit, which had till then been on the decline, suddenly increased. The limit for the aforementioned loans was raised to two crore rupees in 2013.

Basic Statistical Returns of Scheduled Commercial Banks, various issues.

In 2015, the RBI made major changes to PSL rules. It removed the targets of 13.5 percent direct agricultural credit and 4.5 percent indirect credit and replaced it with a single target of 8 percent to small and marginal farmers. This was supposed to be achieved by banks in a phased manner by 2017. However, as of December 2016, credit to small and marginal farmers only forms 4.3 percent of total bank credit. While this can be chalked up to demonetisation, even in March last year, it only formed 5.4 percent as it more or less has for the past five years.

Even if banks manage to meet the eight percent target, it is still too low to fulfill the credit needs of 263 million agriculturalists and laborers.

Commercial banks favour profits over social development. Banking regulations favor commercial banks. And agricultural credit is being driven away from cultivators in rural areas towards large corporations in cities. Yet governments pat themselves on the back for generously allocating lakhs of crore rupees to support farmers each year. Everybody wins, except for the small farmer.