How small workshops on mobile phones are changing governance in tribal Chhattisgarh

People in urban India are calling up government officials in tribal areas, ensuring accountability for governance measures with the help of CGNet Swara

India’s adivasis account for eight percent of its population, and often face deprivation and violence. In the Central Gondwana region (mostly Chhattisgarh), a movement is attempting to improve governance for tribal communities through mobile phones.

How CGNet Swara works is simple: people from the region call up a number, and report any stories they like. These stories are then reviewed and verified. They can also call up the same number to listen to stories being reported from the region.

What are the kind of stories people report over this portal? Devansh Mehta, Head of Urban Outreach and Business Development at CGNet Swara, says that apart from stories about governance issues, people also call up to record songs, folktales, and the like.

Since its formation in 2010, CGnet Swara has logged over a million such phone calls and published 10,000 reports.

But the big question is what to do with the reports when they mention specific grievances. CGNet Swara does not want to go and solve the grievances themselves.

Mehta explains, “The idea is to make the existing government machinery work better. The model of giving people goods to solve administration problems needs to change because it is not sustainable.”

Thus, when someone calls and records a complaint about a hand pump not working, for example, the first step taken is to ask the caller what they have done to try to solve the problem. If the caller says that their attempts at getting the officer responsible to fix the issue have been unsuccessful, they are asked to share the responsible officer’s number.

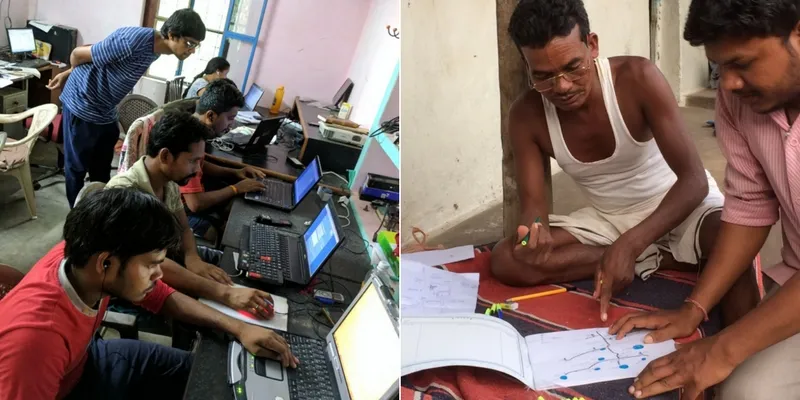

This is where it gets interesting. Volunteers from different parts of the country, and even some based abroad, call up the concerned officer and ask them why the problem hasn’t been solved. “This creates external pressure to solve the problem,” Devansh says.

“We’ve noticed that the farther the call comes from, the more impact it has. A sarpanch in Chhattisgarh does not expect a call from Mumbai or New York asking about one person’s unpaid NREGA wages, and thus gets pressured into solving the issue.”

But what happens when the novelty of calls originating from faraway places wears off?

“The other lever we use is volume,” Devansh says, “Everyone wants to look like the good guy. If you keep getting a lot of calls about an issue, you naturally want to tell the next caller that you have fixed the issue.”

This calling and pressurising mechanism had not been formalized until this September, when CGNet Swara organised a calling workshop in Mumbai. It got together a small group of teachers, college students and other professionals and trained them to call and ask about grievances.

“Initially people were hesitant about making the phone calls. But all the trepidation evaporated after the first phone call.” Devansh says. While a minority of the officers called said that the problem had been solved already, a majority explained where the problem was stuck. The officers were, by and large, helpful.

Rishabh Kathotia, an equities trader who attended the workshop, says,

“You think you are being productive in your day job, but calling someone up and solving a remote problem is just incredible. It’s one of the few activities that are a win-win for everyone. And I would absolutely do it again.”

All the calls made are followed up on with the person who originally recorded the complaint. One way CGNet Swara measures impact is through the number of people calling the phone line to thank them for fixing problems. They receive almost nine such calls every month – a signifier of issues solved to their entirety.

There are plans to scale up this model majorly. The organisation is looking at putting together more such workshops in more cities, and at putting up particularly thorny issues on social media so they get wider attention.

Started by Subhranshu Chowdhury, a former BBC producer and Hindi news reporter, CGNet Swara has been funded by Gates Foundation and the UN Democracy Fund among others. Their next challenge is experimenting with several sustainable models to keep the organisation on a growth path. Chowdhury calls the movement a “mobile satyagraha”: a modern, quicker version of a quintessentially Indian solution.

Ultimately, says Devansh, the idea is to “help people with their fight, not to fight it for them. And once scale our urban workshops up, we are confident that a call a day will keep problems away.”