Locked out of the job market: India’s missing demographic dividend

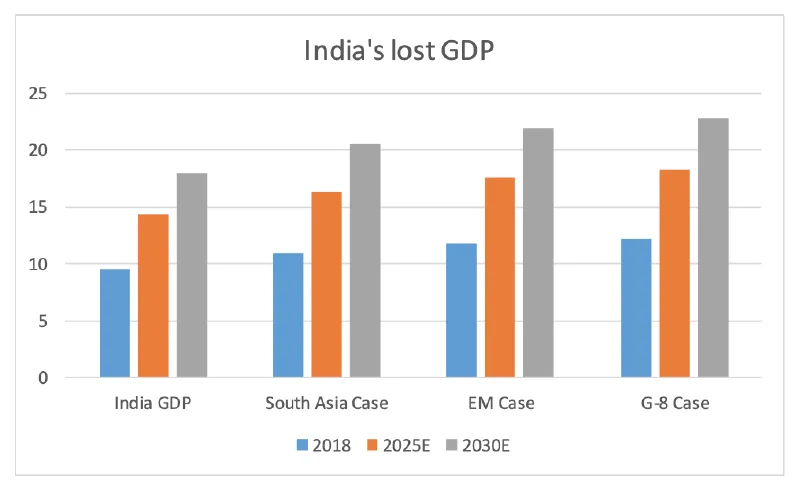

Data suggests India lost between $1.4 trillion and $2.8 trillion in GDP in 2018 due to lower female participation in the workforce. To put that in perspective, this lost opportunity is equivalent to the entire economy of France and Spain.

Demography is not economic destiny. In mainstream economic and business discourse, a key argument underpinning India’s inevitable rise in coming decades is said to be its favourable demography - the country will likely be home to the largest population of world’s youth, at least until mid-2040s. However, strength of institutions, state support to innovation, and above all, the investment in skills to equip the youth for jobs of the future are imperatives without which the demographic dividend just becomes an easy and potent fuel for social conflicts.

Falling economic participation of women remains a red mark on India’s otherwise laudable economic reform report card.

When we talk about India’s employment challenge, an often repeated and ominous statistic is the addition of 10 million new people to the nation’s workforce, every single year, until 2030. This development, which has already been underway since 2010, has been attributed as the reason behind the frequent agitations for caste-based reservations (in a rather less socially segmented Indian society compared to the time of independence), and the rising support for farm loan waivers.

But, what if I said that despite this challenge, the governments of the future may not have to create 10 million new jobs each year? What if a significant portion of such youth would never protest on the streets, rather they will not even actively seek jobs? And what if I told you that, despite this somewhat optimistic scenario, we stand to lose a lot, even in this case?

This article is a preliminary attempt to quantify India’s lost demographic dividend - of the lost potential of millions of women who are simply shut out of the job market; and the impact this could have had on our economic and social well-being.

Women in the workforce

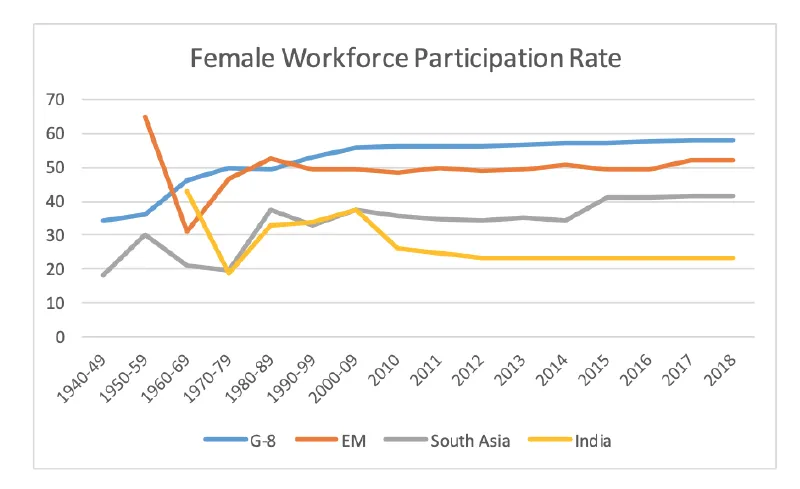

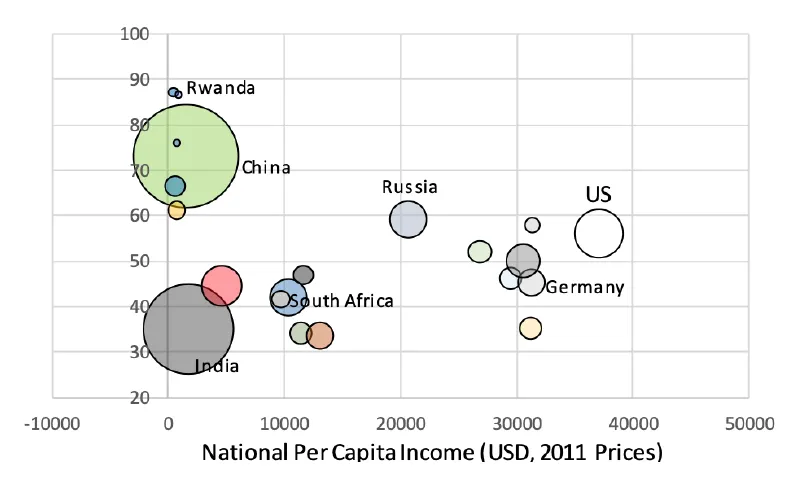

When it comes to female labour force participation rate (LFPR), how does India do, as compared to other countries? As the illustration below shows, unlike other state-endorsed indicators of economic and institutional strength such as Ease of Doing Business and Global Competitiveness Index, where India has notched up strong gains in the past five years, the country’s performance on ensuring fair and equal participation of women in the labour force has been abysmal and shameful.

Not only have we failed to match up to the more advanced G-8 countries in putting more women to work, we also lag significantly behind countries in the same stage of economic development (EM-8) and those with a lot of cultural and social similarity (South Asia). At 23.4 percent as of 2012, India’s

female labour force participation rate (LFPR) trails that of South Asia (41.6 percent), Emerging Markets (52.2 percent) and G-8 (58.2 percent) by quite a margin.

India’s female Labour Force Participation Rate significantly lags other countries, even those that are culturally and economically similar to it (Source: ILO)

If Indian women participated in the labour market at the same rate as other emerging markets, India’s labour force would have been bigger by a number equivalent to the size of Japan’s population.

The fact that approximately 77 percent of women in the working age group in the world’s second most populous country remain locked out of the labour market implies a wastage of human resources, not just on a national, but on a global scale. To quantify this point better, if India’s female LFPR was similar to that of South Asia today, we would have had 78 million more workers (population of Germany); if we were to match the LFPR of Emerging Markets (China, Russia, Mexico, South Africa), we would have had an addition of workers equivalent to the size of Japan; and if India had a female LFPR similar to that of G-8, it would have meant 150 million more workers today.

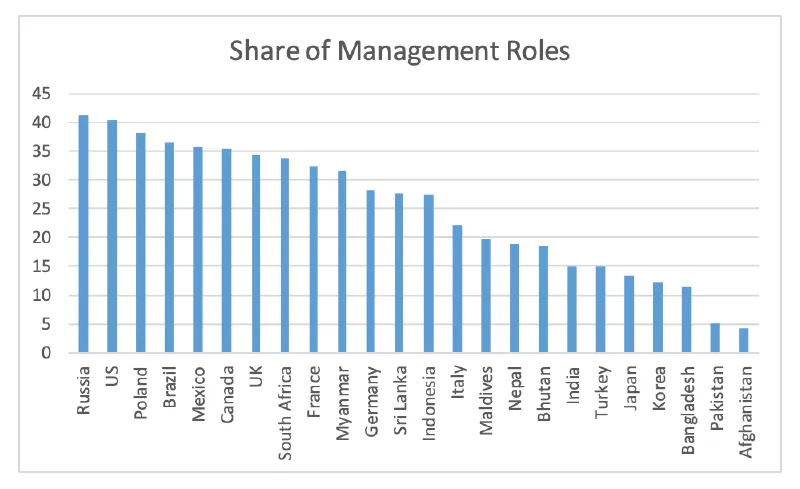

When it comes to CEO and board member positions in the corporate sector, Indian women are better represented than other emerging markets. However, their share in mid-management roles is disappointing, pushing back India’s ranking on this measure. (Source: ILO, Governance Metrics International)

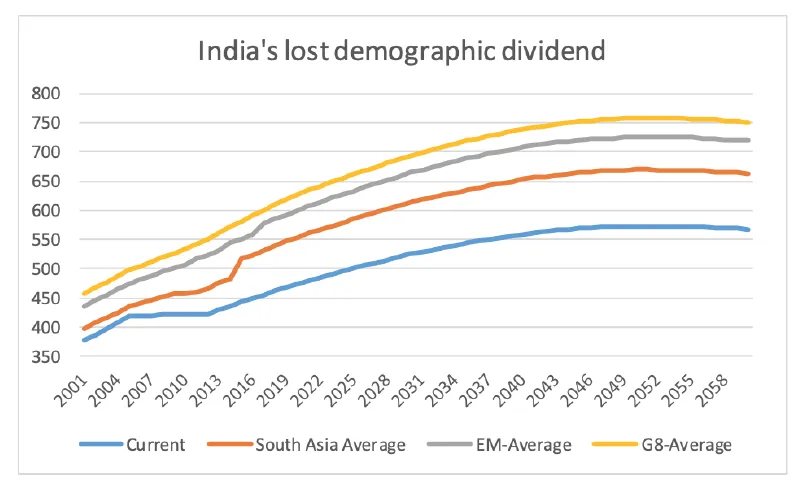

What has been more disappointing in India’s case is that as the country has become more prosperous, the female LFPR has fallen, from 37.7 percent at the time of the 2001 census to 23.4 percent today. Looking ahead, even if the LFPR remains at current levels, as the country’s youth population expands, we could have anywhere between 90 million and 170 million missing workers in the economy, as women voluntarily or involuntarily choose to stay out of the job market. For those of us who believe that demography is destiny, this missing dividend should highlight the enormity of a lost opportunity.

India’s workforce could have been 20-30 percent larger if it had similar levels of female LFPR as other emerging markets. (Source: OECD, ILO)

Impact of shutting women out of the workforce

Since a number of us tend to measure a country’s economic might in terms of its GDP, it would be useful to quantify the GDP impact of a lower female LFPR. I use the Conference Board database on GDP per worker and attribute a 6 percent y-o-y growth rate in labour productivity (the trend over the last the years) until 2030. Furthermore, I assume the counterfactual scenario in which a female worker currently out of the labour market, if trained and employed, would have had the same productivity as an average worker currently in the labour force.

Given these assumptions, in 2018, India lost between $1.4 trillion and $2.8 trillion in GDP (PPP, Constant 2016 prices) due to a lower LFPR. To put that into perspective, this foregone opportunity is equivalent to the entire economy of France and Spain.

The costs of lower LFPR over the coming decade are even heavier. As the illustration below shows, the Indian economy will be between $2.5 trillion and $5 trillion smaller if the women’s workforce participation continues to languish at current levels. The potential loss to GDP could probably be even higher from the productivity boost firms receive from gender diversity.

India currently loses a GDP equivalent to the size of the French economy by keeping women locked out of the job market. (Source: Conference Board, OECD, ILO)

A cross-sectional study of female LFPR shows that when countries move from agrarian to industrial economies, the participation of women in the economy initially falls.

The earliest available census data on India’s female LFPR comes from the 1961 census, which shows it to be at 42.9 percent. Thereafter, the LFPR stabilises at 30-35 percent for the next 40 years, followed by a sharp decline from mid-2000s to the current level of 23-27 percent. To an extent, some decline in female LFPR is expected in any economy that undergoes rapid industrialisation. Part of it is due to the way in which industrial work and corporate hours are structured; part of it is due to the way in which GDP is measured (ignoring the value of unpaid work).

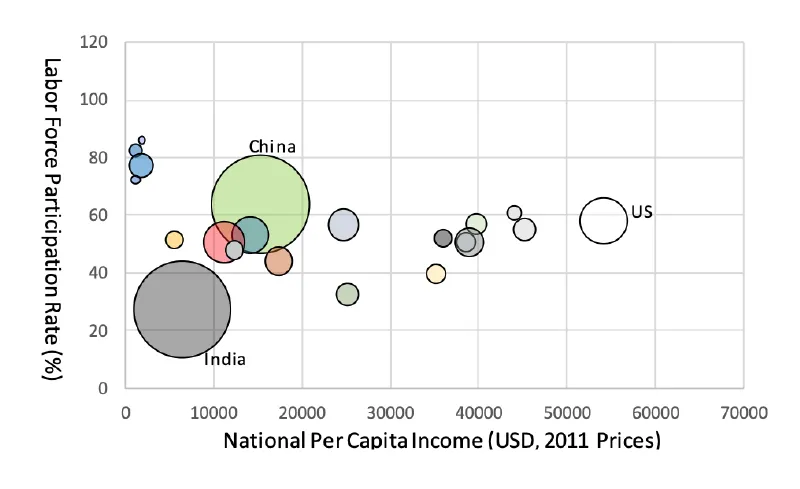

The world in 1990, when China and India were still under-developed and had a relatively larger share of women working.

Some signs of a U-Curve. China and India have lower female LFPR but are richer; Italy and Mexico are on the rising arm of the U-Curve. (Source: OECD, World Bank, ILO)

In a widely cited paper in 1994, Claudia Goldin showed the tendency of female LFPR to follow a U-Curve as the economy develops – women’s participation remains high in a pre-industrial economy; it declines when the economy starts to move towards factories located away from homes and with fixed working shifts; and it again begins to rise when the economy starts to move towards high-skilled service based jobs and when investment in education has enabled a generation of women to seek diverse and more remunerative employment opportunities, which become relatively more attractive to staying at home.

Looking at a cross-section of countries between 1990 and 2017, this hypothesis does seem stronger.

The illustration above plots female LFPR against national per capita income. In general, the female LFPR in industrialising middle-income emerging markets such as South Africa, Mexico and Turkey was lower than that of the LFPR in low-income, natural resource driven or agrarian economies such as Mozambique, Rwanda and Ethiopia. Furthermore, as the per capita income rises, as seen in the case of China, Myanmar and Turkey; female LFPR has fallen between 1990 and 2017.

On the other side, countries like Korea, Mexico and Brazil, which were already on the verge of middle-income threshold in the 1990s, saw the female workforce participation rate increase over the next two decades, as the contribution of retail, trade, community, social and business services increased in the economy, which tend to employ more workers than mining and assembly-line manufacturing.

If female LFPR tends to follow a U-curve for most economies, should we be worried about the fall in India’s LFPR over the last 15 years? Should we assume that over time, as our women become more educated, their participation in the economy will increase? Will faster globalisation also help?

That said, Female LFPR may not follow a U-Curve even as the country grows richer, especially if the social and institutional frameworks are not supportive.

The U-curve looks comforting. However, correlation does not always imply causality. There are two fundamental problems with the U-Curve.

First, the U-Curve hypothesis wrongly assumes that female economic participation depends on national per capita income. What if the rapid increase in female LFPR in Latin American and South East Asian economies itself was the reason behind the increase in national per capita income? Is it possible that the governments and society in countries like Mexico, Brazil, South Africa and Indonesia created laws, work environments and institutions that allowed women to participate more actively in the economy, hence leading to more economic prosperity?

Furthermore, there are countries such as Turkey which got richer in the last three decades, relative to some of these star performers, but yet saw a decline in female LFPR? Even among advanced economies, the LFPR for women in Japan has barely moved in the last three decades, and their share in senior management positions has remained lower than both in China and India, despite the national income per capita today being almost 30 percent higher than it was in 1990. Clearly, an increasing LFPR as the economy grows and diversifies is not a given.

Women and the economy

One underlying rationale behind a positive relationship between female LFPR and higher per capita income is that improvement in female health and education, alongside easy availability of credit and reduction in the opportunity cost of housework usually accompany fast economic growth.

Improvements in health services and reduction in maternal mortality rates reduce the burden of disease and disability that employers face when hiring women. Higher educational skills improve their long-term employability.

Easy availability of credit encourages women towards self-employment, arranging their lives around their children. Finally, economic growth also increases the supply of household appliances such as refrigerators, washing machines, cooking stoves and cleaners, which automate and drastically cut down the time taken for housework.

Indeed, these were the factors that doubled the female workforce participation in the US between 1940 and 1980. However, could there be a case, where despite such positive factors affecting the well-being of women, the female LFPR continues to decline? Is there a situation, where possibly, despite being more educated and healthier than their mothers or grandmothers, women still could face invisible barriers to economic participation? Is India facing that situation?

Women’s participation in the workforce is not just a function of economic growth, but of its composition too; India’s growth path is likely to create less jobs in sectors that have traditionally employed more women.

More nuanced studies on LFPR show that women’s participation in the workforce is not just a function of economic growth, but also the composition of economic growth and employment opportunities. In India, agriculture remains the largest occupation, and the largest employer of women.

As the economy progressed and agriculture became more mechanised, agriculture lost 35 million jobs in the 13 years since 2005. Of this, close to 24 million workers were women.

Unfortunately, employment growth for female agricultural workers has been insufficient to compensate for this loss. Other nations that made the progression from an agricultural to a modern economy found different ways to make up for the female workforce participation that was lost due to mechanisation of agriculture and animal husbandry.

Notably, by becoming the garment manufacturing and assembly centers of the world, countries like Vietnam and Ethiopia maintained female LFPR rates close to 70 percent. In the case of Bangladesh, which saw women workforce participation rates rise from 3 percent at the time of its independence in 1971 to 36.4 percent today, much of this improvement has come from better access to credit, which has helped them set up small businesses, enabled them to invest in their skills or take care of family emergencies, allowing them to become more active and able participants in the country’s booming export sector.

When it comes to gender equity in the economy, India and Pakistan have much to learn from Bangladesh.

Meanwhile, the acceleration in female LFPR in Latin America in the 1990s and early 2000s came from an increased number of job opportunities for women in organised retail, hospitality and community services sector (teaching and nursing).

In this context, India’s female LFPR growth remains at risk. India seems to have lost the opportunity to capitalise on labour intensive manufacturing, which has moved out of China.

As a recent report by Bloomberg pointed out, countries in the Southeast and East Asia have been net beneficiaries in terms of FDI following trade disputes between US and China as firms have gradually moved manufacturing supply chains to countries not so strongly limited by US import tariff barriers. The impact of this shift on FDI investments in India has been negligible. That said, foreign investment continues to pour into India, but largely in software and IT services, telecommunications and business services.

However, jobs created in these sectors catered to high skilled and highly educated segment of the workforce, which is disproportionately male. At 26.7 percent, India’s share of female population enrolled in tertiary education remains below the global average of 40 percent. Second, unlike other emerging markets, India remains under-invested in healthcare and education, which tend to be the major employers of women when an economy moves from a low-income to a middle-income phase.

Furthermore, as automation replaces labour intensive jobs in the coming decade, the first casualties will be the labour-intensive jobs that led to faster growth in female LFPR over the last three decades in other emerging markets. Therefore, in many ways, automation induced inequality is likely to hurt women more than men since they tend to be less educated relative to men, and remain at a greater risk of being driven to obsolescence by automation.

Cultural norms limiting women at work

Cultural norms can be a powerful factor limiting LFPR; especially as in South Asia, the domestic and household expectations from women are higher than elsewhere in the world.

Cultural norms are the second factor that impede a greater female LFPR. While LFPR-based estimates portray India to be an intensely gender-unequal and oppressive society towards women, this would still be a one-sided judgment that ignores the marked progress the country has achieved in women empowerment in the 21st century.

Female literacy rates have gone up from 18 percent at the time of independence in 1947 to 62 percent in 2011. Maternal mortality rates and fertility rates have also seen a decline. As the National Family Health Survey 2017 noted, compared to countries with similar economic development and income, the percentage of Indian women who said they were in control of their health and reproductive decisions was 8.2 percentage points higher.

As per the Economic Survey 2018, India registered a similar outperformance relative to its peers when it came to empowering women to be the primary decision-maker on household purchases and expenses. However, the gains on these dimensions were almost offset by a lower than average workforce participation rate for women and on their ability to make career choices and professional decisions.

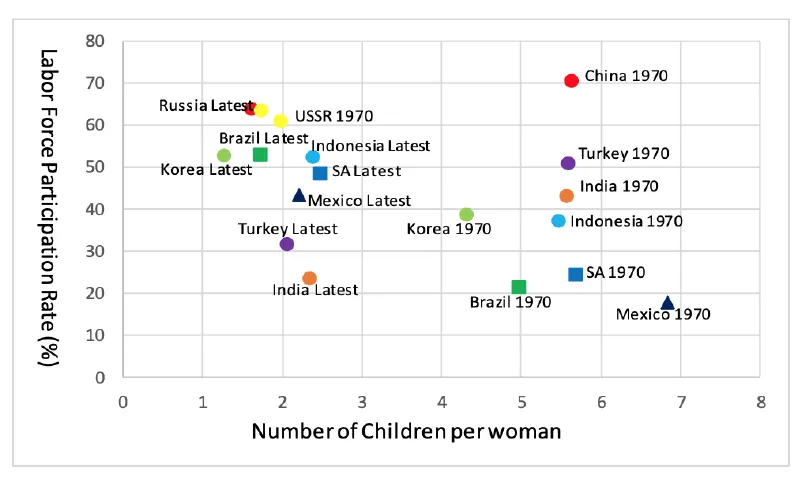

India and Turkey are the only countries where female LFPR did not rise as the number of children per woman fell; cultural norms bound women to households even though childcare time was lesser now. (Source: World Bank)

Seen in this light, the data implies that while the modern Indian society is ready to empower and give greater responsibilities to women within the confines of the household, it remains reluctant to let them step out and enter the labour force. Employment for female members of the household is usually seen as a desperate option undertaken in financial distress. The effect of cultural norms on limiting female LFPR cannot be underestimated. In the case of Japan, much of what holds back female participation is a carryover of cultural norms from the feudal times, which assumes women are best-suited to child-bearing and domestic responsibilities, which are often unpaid.

Moreover, where India’s cultural norms become even more unfavourable to female LFPR relative to other family-oriented societies in Asia, is in the way in which the duty of the women is understood. For instance, in China, Korea and South-East Asia, domestic responsibilities such as childcare and household chores are shared between the elderly in the household and the prime aged female of the household (in most cases, the daughter-in-law). That participation is much less in India’s case and is considered culturally less acceptable.

In South Asian households, the expectations are to take care of both the elderly parents, in-laws and children, without much assistance from other members of the extended family. No wonder then, that employment is seen as an option of last resort. This may perhaps explain the reason why states in Northern and Western India have seen the sharpest decline in female LFPR as they have raced ahead of the others economically. Women there have chosen to use the increased household income to buy more free-time and mind-space, allowing them to concentrate on domestic tasks that are socially perceived to be more central to their role, though not equally remunerative.

Therefore, it remains a question as to whether the higher enrolment of women at the school and college levels seen since 2003 will actually result in higher participation of women in the economy. Or, will they continue to turn down a paying career to become dedicated home-makers serving parents and children?

The point of this argument is not to belittle the contribution of the Indian housewife, or to look at the culture pejoratively. Domestic work could be immensely fulfilling for women, as well as men. However, it needs to be offered as a choice and not as a cultural norm. And the opportunity costs it imposes on economic growth must be understood.

Lack of credit, poor public safety and inadequate investment in public transport are other reasons which inhibit female LFPR growth through a rise in entrepreneurship; which has been a powerful source of employment among women elsewhere in emerging markets.

Finally, even when families that are willing to support women at work in India, finding a good and fulfilling career remains a challenge. Multiple factors dissuade women from achieving their potential, especially if they decide to become self-employed. Access to credit remains a challenge, given that as per the EIU, less than 13 percent of women in India hold any assets separate from their spouse or family, which could be pledged against a loan. Second, underinvestment in public transport infrastructure means women who wish to arrange their lives around their children and parents-in-law have a difficult time commuting between home and office (they are also less likely to own a vehicle).

Perforce, they end up taking part-time jobs or resign, which could severely impact their sense of self-worth. As Satpal, Rathee and Rajain (2014) noted in a paper, women entrepreneurs also find it difficult to engage in business travel, rent hotels in Tier II and Tier III towns, and be taken as serious and committed professionals by investors.

When safety is key

Another limiting factor, as noted by World Bank, is the lack of safety, particularly when working late hours. In the absence of better policing, the response of the corporate sector towards ensuring safety for women has been to bar them from overnight shifts and to overlook them for assignments that require collaboration in real-time with clients in the US or Europe. Compounding the misery is the attitude, held by 84 percent of Indians, as per a Pew Survey, that there is a limited number of jobs available in the economy, and that women should not take them away from men, who have families to support. This mentality implicitly assumes that 150 million women locked up in their houses could pose a threat to the already scarce jobs in the economy, rather than creating more of them.

So far, the approach of successive governments in India towards gender equality has been driven by a welfare-approach rather than an empowerment approach. Central and State governments have taken laudable steps to reduce the burden of housework (subsidised LPG connections and distribution), limit the time spent to look for water, increase enrolment and benefits for natal and post-natal health.

That said, the bias has been towards “caring” for women, rather than “enabling” them; something that is implied by the fact that we still have a Ministry of Women and Child Development, hinting that both these vulnerable groups require some kind of state protection.

The need to boost female LFPR has more to it than economic pragmatism. Work that is gainful and remunerative has a positive psychological impact on people. It enhances their self-confidence, pushes them to discover their abilities and allows them to strive for their ambitions. This is why, its absence, whether enforced by cultural or institutional norms, is a gross denial of human rights. No amount of agency, wealth and prosperity transferred to women within their households today can be an excuse to deny them a choice of a career.

Also read: China-US Trade War: More of the same, after the temporary truce