Across India, women are struggling to deal with the growing infertility problem

Despite increasing access to infertility treatment services and specialists, dealing with infertility is one of the toughest challenges that women across India face.

The world’s second most populous country is now coming to terms with a problem it finds hard to acknowledge: infertility.

The World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision estimated that the fertility rate of Indians (the number of children born to a woman) plunged by more than 50 percent. The crude birth rate has gone down from 36.7 births per thousand population during 1975-80 to 18.9 during 2015-20. The report projects that the rate will nosedive to 18 by 2025-30, and drop further 12.1 by 2045-50 and 9.3 by 2095-2100.

A fertility rate of about 2.2 is considered the replacement level (the rate at which the population will hold steady).

Across India, couples are facing the infertility heat.

The Indian Society of Assisted Reproduction says as many as 27.5 million couples—about one in six couples—in urban India are impacted by infertility. AIIMS believes that about 10-15 percent of couples in India have “fertility issues”.

The Indian infertility diagnosis and treatment market is pegged to grow at a compound annual rate of just 12.5 percent between 2022 and 2028, according to a study published by Orion Market Research.

India’s infertility problem

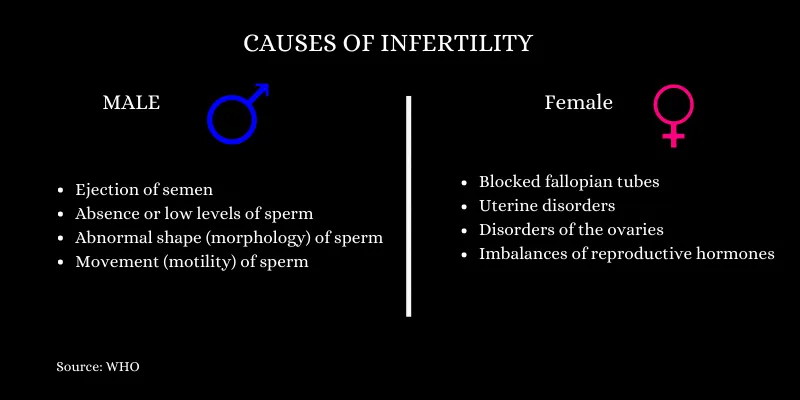

The WHO defines infertility as “a disease of the male or female reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse”.

Infertility can be caused by a number of varied factors, in either the male or female reproductive systems.

It could be either the man or woman who has a problem, but in India, the woman is usually held responsible. It becomes a personal health issue, leading to financial and emotional stress and social stigma.

Very often, women find it tough to come to terms with the fact that they are infertile—that appears to be the bigger challenge rather than seeking treatment.

Dr Rajalaxmi Walavalkar, Medical Director, IVF Consultant, and Endoscopist at Cocoon Fertility, says a woman’s self-esteem and confidence are largely tied to her ability to procreate and “the taboo around infertility is first built up in her head as much as it exists in society”.

“Just because their periods are regular, women think it is a natural process that they are born for. When they are not able to conceive, it starts becoming a taboo in their head. They neither talk to someone nor research in their own time,” she tells HerStory.

The fears stopping women from even looking up infertility and related problems online are many—some are worried about their husbands finding out that they are infertile (through search history); others fear their infertility may cause the husband to remarry.

“We observed the latter fear is especially prevalent among women from some Tier-II and III cities. Many women worry that husbands may remarry as they are unable to conceive,” says Diana Crasta, Chief Psychological Counsellor at Nova IVF Fertility.

However, the problem exists in metros as well.

Rajalaxmi says she met a woman in Mumbai, whose mother-in-law had threatened that her husband would remarry if she did not conceive within a year.

Many highly educated, progressive couples who have been married for more than a decade also often find it hard to open up to each other.

Snneha Lukaa ran a healthtech platform simplifying and facilitating infertility treatments from November 2020 to March 2022. Helping people from both metro and Tier I and II cities seek fertility treatment showed her that “family pressure and spouse pressure of remarriage, especially within uneducated families, are well alive”.

Spreading awareness is making a difference, she says, but the cost involved prevents many from seeking treatment. “People want to but step back due to heavy costs,” she says, adding that her upcoming venture in the fertility space will address all aspects including spreading awareness and finance needs.

Meanwhile, Rajalaxmi says that while finance may be an obstacle for some couples, it is definitely not the biggest challenge. She believes the taboo looms large despite her clinic giving generous discounts and often treating those in dire need for free.

Priya and her husband, both school teachers in Karnataka, started exploring IVF treatments in Bengaluru a couple of years back and had a healthy baby boy last year.

“We were able to take that step seeing a colleague of ours succeed and have their own baby. We felt that if it was really a possibility, then it would be worth all the trouble. But the journey has not been easy. We informed only a few people, knowing those who do not know would only raise eyebrows and gossip about it,” Priya says.

Everybody weighs in

Rajalaxmi says most times a woman ends up in front of the gynaecology or fertility specialist, without having much say in big, life-altering decisions.

In many cases, women are not asked if they are ready for pregnancy. There are often tussles between the mother-in-law and maternal family over the choices of doctors/specialists. If family members are funding the treatment, they usually get involved in each and every step, exerting undue influence on the decision-making process.

Several working professionals in metros often find a way out by not informing family members of IVF treatment/procedures till the pregnancy is guaranteed. Some often never inform them of procedures at all because conservative families view them as “unnatural”.

A popular myth surrounding IVF is that the child is not their own due to “external intervention”.

The Indian Society of Assisted Reproduction says about one in six couples in urban India is impacted by infertility.

The need for awareness

Many infertility specialists comment on the lack of awareness of the cause and treatment of infertility, stating that it costs people years, money, and serious life decisions. Most importantly, men often don’t understand that “they can be infertile as well”.

Rajalaxmi recalls meeting a man who married for the third time in the hopes of bearing a child. The blame for lack of conception rested with his wives; he was not tested at all.

“It turns out the man was infertile and refused to get tests done. He asked how it could be him as he was able to have sex,” she says.

Other couples seek Ayurvedic solutions or turn to general practitioners.

Diana says another problem in dealing with infertility is that reaching out to specialists is seen as the last resort—after investing significant time, money, and energy elsewhere. By the time they reach infertility specialists, couples, especially women, are mentally exhausted.

Rajalaxmi also emphasises on the importance of “reaching out to the right doctor at the right time”. She recalls a woman who visited her clinic after trying out 21 IUI treatments (which involves placing sperm inside a woman’s uterus to facilitate fertilisation), and says nobody had bothered to check whether her fallopian tubes were open.

"Both her tubes were closed. Somebody should have checked the tubes before the first IUI and told her that no sperm could reach the egg," she says.

Another couple, married for 15 years, came with 26 files showing the wife had gone through ovulation induction repeatedly for the last 10 years.

Ovulation induction, which stimulates ovulation through medication, is normally done a maximum of four to six times.

“When the patient came to me, their ovaries hardly had any eggs in them. The success rate is very low in such cases. Visiting a fertility specialist can make all the difference. This is like a cancer patient going to a general physician even after the cancer is diagnosed,” she says.

“Education and awareness are horribly lacking…the things you see in this field are horrible. I have seen so many things, sometimes it brings tears to my eyes,” the doctor adds.

Tackling the taboo

Infertility specialists say things are changing, albeit at a very slow pace.

Diana, who has been counselling couples for the last six years, says more people are coming forward to assess treatment options, making infertility less of a taboo.

Rajalaxmi also agrees to “a gentle social shift in the last couple of decades”.

However, the biggest solution lies in assuring girls that they are worth more than their ability to conceive and creating awareness that both men and women could be infertile.

“Unless every girl is told that becoming a mother is not a final goal of her life and that infertility is not the end of the world, the next generation will go through the same suffering that women face today. People may look down but the worst thing is women start looking down on themselves,” Rajalaxmi says.

Edited by Teja Lele