Women in workforce: What it would take to achieve gender parity in India

Bengaluru-based Preethi* is a smart and driven young woman who moved to the city after her marriage to live with her husband and mother-in-law. Following her move, Preethi, who is now the proud mother of a nine-month-old, had enrolled in a three-month sales training course in the city. The course had landed her a job at a high-end watch brand located 10 km away from her home. Unfortunately, her mother-in-law fell ill soon after, and with no other support system in place, it became impossible for Preethi to continue working. And so, Preethi was forced to do the inevitable: leave the workforce so she could care for her child and her mother-in-law. Recently, when we quizzed Preethi’s husband about the possibility of her returning to the workforce, his only question was, “Who will take care of our baby?”

Preethi’s story, in all its familiarity, is the story of the majority of Indian women today – one that is hardly likely to raise an eyebrow.

“A woman’s first responsibility is to her home and family”. “So what else do you expect? The husband to stay back and take care of the baby?” These are some of the remarks and questions that most Indians take for granted in discussions centred around the Indian woman’s role in society.

This, despite the fact that we’re now in the 21st century, or that women all over the world are breaking new ground in every arena of life and work. As a matter of fact, every few months, the dismal status of women’s participation in the Indian workforce makes headlines, only to be quickly swamped by the flurry of other news and information available in the market today.

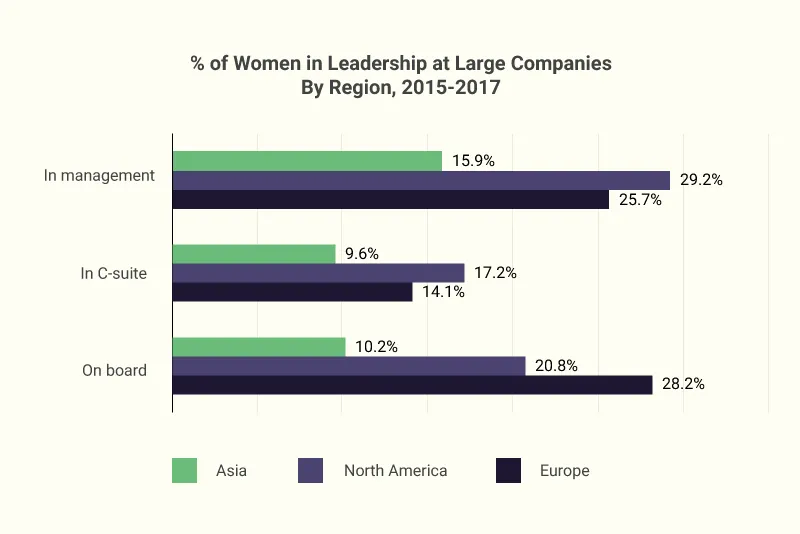

Still, even though the 2017 India Development Report from the World Bank ranks India a shocking 120th out of 131 countries in the world on female labour-force participation, across the world too, the share of women in the formal workforce, especially in senior positions, has continued to remain low. Out of 1,500 large public companies listed across 27 countries analysed by Quartz, 95 percent of companies are led by a significantly male-dominated management, with this phenomenon particularly evident across management levels at Asian companies. In India, women account for approximately 17 percent of senior management.

Source: Quartz; Data: Gender Diversity Exchange

Social justice or business case?

Gender parity has long been touted a feminist agenda with social justice an end in itself. However, more recently, the business case for gender diversity is gaining some prominence.

The 2017 World Bank report goes on to make the macroeconomic case for increasing the number of working women in India by showing that an increase in the participation rate from the current 27 percent to 50 percent could boost India’s overall growth rate by 1.5 percent. McKinsey Global Institute has done further research to show that in India, women’s contribution to the GDP stands at just 18 percent, far behind China, where women contribute to 41 percent of the total GDP. Only Pakistan, where women contribute just 11 percent to the GDP, is behind India. If McKinsey’s estimates are accurate, India can add a mind-boggling $770 billion to its GDP annually simply by achieving gender parity in the workforce. No wonder then that the “Women First, Prosperity for All” theme dominated the proceedings of the Global Entrepreneurship Summit 2017.

Research at an organisation level has so far been restricted to the developed economies and mostly at the senior management or board level. A Catalyst study in 2017 found that companies with the highest number of women in the top management perform better, both in terms of Return on Equity (ROE), which is 35 percent higher, and Total Return to Shareholders (TRS), which is 34 percent higher. Another study by Catalyst found that across five industries, companies with the most number of women board directors outperform those with the least, based on a 26 percent increase in ROIC. Similarly, a 2014 Gallup study of more than 800 business units from two companies representing two different industries -- retail and hospitality -- showed that gender-diverse business units had 14 percent higher average comparable revenue than those dominated by one gender.

In India, there has been limited research and data surrounding the business case for diversity. However, Sattva’s work in the field of employability and gender in India has brought to light several significant anecdotal evidence. For example, in the case of customer experience roles, employers see tangible benefits in hiring women.

“50 percent of our consumer base is women. Women understand women best. And by having more women in our workforce, we are able to cater to a large consumer segment more effectively,” was a sentiment echoed by HR across industries such as retail, hospitality and wellness during a customer experience roundtable held by Sattva. “Women and men both love buying from and engaging with women. They are more empathetic to the customer need, more patient and pleasing. The business case for us is very clear.” Similar strong evidence has been pointed out in other studies when it comes to women in sales.

In general, diversity and inclusion experts (not specific to gender diversity alone) have been making an increasingly convincing case with respect to hard business metrics such as revenue, profitability, productivity, customer satisfaction and retention, as well as with other critical parameters such as the quality of innovation, creativity and better decision-making, which are more intangible benefits.

Unpacking the profile of women in the workforce

One of the most interesting observations about the participation of Indian women in the workforce has been the almost inverse relationship of female workforce participation with economic well-being, i.e., women tend to drop off from the workforce as the household economic situation improves. While India has made steady progress from 1990 to today on the economic front, women participation in the workforce has worsened from 34 percent to the current 27 percent.

The graph below shows the sectors with the highest participation of women. Besides agriculture, manufacturing, especially food and textile manufacturing, appear to attract the highest number of women, as do education and retail sectors within the services industries. This is likely because these sectors – food, clothing, education, and services or front-desk – are also the fields that have traditionally been more aligned to society’s expectations of women.

As per the last census, rural women workforce participation is higher across age groups versus urban women. There is also a clear caste difference with a higher participation of SC and ST women versus other forward castes, which could possibly mean most women work out of economic necessity.

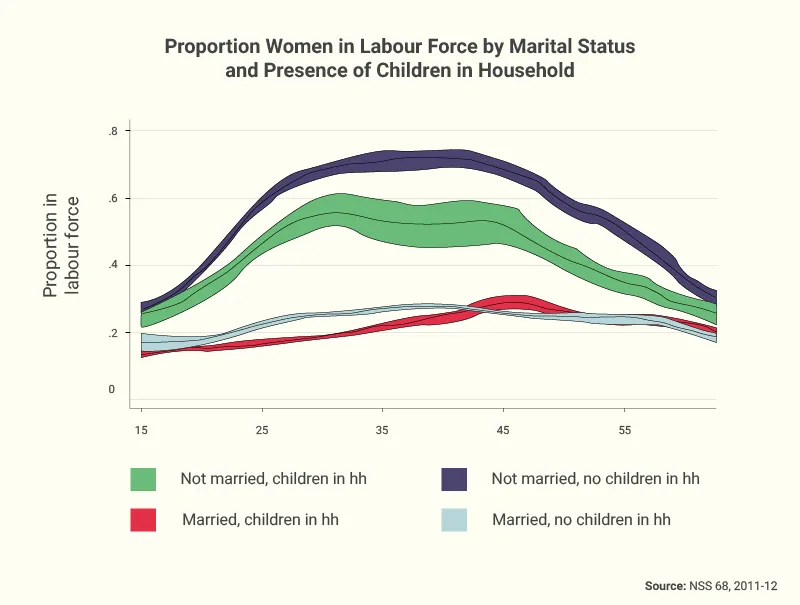

Rohini Pande et al, in their 2017 paper “Women and Work in India: Descriptive Evidence and a Review of Potential Policies,” also point out that married women are more likely not to work, irrespective of whether or not they have children. Presumably, single women without children have the social freedom to work, while single women with children have an economic necessity to do so, even as married women have more responsibilities inside the house as well as different societal norms to follow.

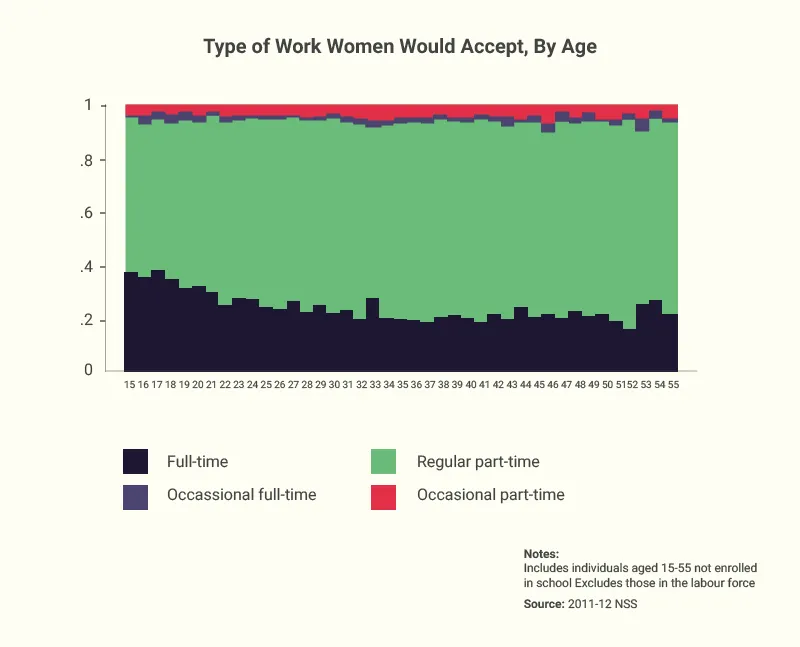

The Rohini Pande paper provides another interesting insight, in that, despite the barriers and the current social paradigm, women are still interested in having a “regular” job, rather than some occasional work. Yet, there is a definite preference for a steady and predictable part-time work versus regular full-time work as shown in the figure below.

What are the barriers for women in India to work?

Through Sattva’s multiple skilling and livelihood programmes aimed at women, one of which was aimed at creating opportunities for underprivileged women to work in high-end retail firms, it became increasingly evident that the lack of skills is only one of the many barriers Indian women face in joining the workforce. The programme, which focused on building the skills of 12th pass and graduate women in retail sales, saw a number of success stories of women getting access to decent jobs with high-end brands and continuing to grow in their careers. However, it became clear very soon that bringing women into the workforce is a complex, multi-dimensional problem, and the following section captures some of our learnings from the programme.

1. Lack of agency in making career decisions

Much has been written about the patriarchal culture of India, which is evident across most communities. For unmarried young girls, parents are still the decision-makers when it comes to education or employment, and most parents continue to view it their primary duty to get their daughter “married off”, with employment, in general, and sales-related roles, in particular, only serving to complicate marriage prospects.

“My parents are worried that I might not get a good marriage alliance if I work in retail”, says Arpita* from Thane, who had to fight a battle at home before her parents agreed to let her join the course.

One woman* articulated this well: “My husband expects me to take care of the home, and his job is to bring home the money. He feels that if I work, he will have to take care of some of the things at home, which he thinks would make it difficult for both of us. Things are working well the way they are.” In other words, for many women, crossing the hurdle of going against the family is just too much trouble.

2. Lack of sufficient role models amongst women a deterrent

While it’s a well-known fact that the large majority of Indian women are not the primary decision makers in the family, it’s a lesser known fact that many of them do not view working as something aspirational nor of holding any personal significance. The primary reason for this is a lack of relevant role models for women, no matter what their background.

The few well-known successful women seem too far away from their reality to serve as effective role models. Often, this lack of aspiration is dismissed as “but women don’t want to work” and justified as a choice women make independently. However, more often than not, women are conditioned to think in ways that are aligned with the prevalent norms.

To tackle this problem early on, many non-profit organisations such as Voice4Girls, Antarang Foundation, and DreamADream, amongst others, are giving young girls the opportunity to dream big by showing the benefits of agency and choice at an early age. However, this lack of aspiration and early thought conditioning towards working outside the home, especially in male-dominated fields, remains one of the biggest roadblocks in improving the participation of women in the workforce.

3. Lack of support systems

Unsurprisingly, the lack of suitable support systems such as child-care or elder-care is one of the biggest barriers for women to work. By design, our work systems are not built to provide the flexibility that is critical for a woman, especially during certain life-stages, and working part-time often translates to stagnancy and low growth opportunities. Interestingly, families become more supportive of women working post-marriage and after having children, as it becomes an economic imperative at this point to have a second income for the household.

However, in the non-agricultural sector, apart from jobs such as teaching, home-tuitions, and some factory jobs, it is not very easy for a woman to take up a regular, full-time job outside the house, given that the majority of the household and childcare responsibilities fall on the woman.

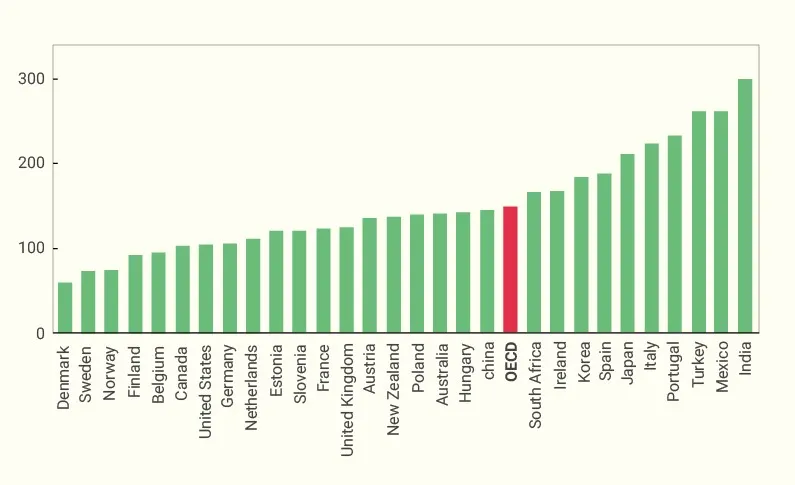

As per a UN report, Indian women do more than 300 minutes a day of unpaid work compared to men. The silver lining in this is that come January 2019, the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) will measure domestic work to better understand how women contribute to the nation’s economy. Secondly, the Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, 2017, brought about a number of beneficial changes, including 26 weeks of paid maternity leave and mandatory crèche facilities in establishments employing more than 50 employees. Implementation of the Act remains to be seen.

Women do more unpaid work than men, minutes per day

Source: UN Report (Why unpaid female labour matters: How to use Time Use Studies to evaluate it?)

4. Lack of women-friendly employer policies

In our experience, we found that women tend to be enthusiastic about skilling courses in retail, but many tended not to take up these jobs once the time came for them to join the workforce.

This is usually due to three main reasons:

- distance of the workplace and time taken to travel from home

- long working hours and unfavourable shift timings, and

- issues of workplace harassment and implicit bias and attitudes towards women.

It is no surprise then, that there are not enough women in most job roles as organisations are not trying hard enough to make them work for women.

In our programme, we also found that sexual harassment laws were often not explained clearly to women employees, and franchisee stores were not monitored regularly on their implementation of harassment policies. One of our students* was abused verbally with sexual innuendos by her immediate superior, which caused her to abstain from work for extended periods of time without providing any reason for her absence. Being the primary earner in the family, she was afraid to make this an issue, fearing the loss of her job. She confided in the programme managers and the issues were resolved with the HR and the franchisee owner in a tactful manner.

However, not all women are lucky enough to have someone mediate on their behalf. So, even as a number of employers are today investing in diversity consulting, with surveys such as “Best Companies for Women in India” finally providing data around this subject, it must be noted that these investments in inclusive policies and systems are largely restricted to large, formal sector employers.

5. Lack of employable skills

Many Indian women, especially from marginalised communities, are married off at an early age, soon after they complete their schooling or graduation. Many of these women aspire to re-enter or join the workforce after they have their own families or their children have joined school. For this segment, there is a notable gap in employable skills due to the long break in their careers or from never having worked in the first place.

One of the candidates from our retail programme Jayanthi,* who is now the mother of two children, was working in retail sales until her first child was born. When she came into the programme, Jayanthi was an under-confident woman, without any active networks and was completely disconnected from work expectations in retail roles. The course, with the intensive mentoring provided by the trainers, helped fuel Jayanthi’s aspirations, prompting her to seize the opportunity to work and land a job at a leading QSR brand.

Accessible platforms for skill development, which enable entry/re-entry into the workforce, combined with counselling and mentoring programmes, become critical for women like Jayanthi looking for avenues to bridge the gap in their employability.

Workplace diversity: cost or investment?

For most employers, focusing on diversity in the workplace immediately signals the need for upfront investments in terms of policies and support services, in addition to training. To cite an example, there is an organisation that trains women to become drivers and they impart driving plus customer engagement skills. While this potentially highlights a large market opportunity, given the number of crimes against women by male cab drivers today, the cost of training women is at least twice that of training men. A little digging told us why. In almost every case, women have multiple responsibilities at home – primarily cooking, child-care, and elder-care apart from the dozen other things they have to do. Taking time out to acquire employable skills requires working around these schedules and responsibilities, which typically means fewer hours per day and hence lower trainer utilisation. All of these result in higher cost of training while entering the workforce.

As one goes higher up the ladder, an employee would necessarily have larger responsibilities. For example, in fields such as retail and customer service, the store manager is required to stay back beyond the last shift to tally the accounts and the inventory or assume the task of managing more than one branch or one team. This, in turn, forces women to reconsider their choices and, more often than not, resign themselves to quieting their own ambitions to be better able to deliver their household responsibilities and avoid disturbing the family dynamics. Enabling women to perform these roles would mean providing extra support to handle their responsibilities at home (e.g. childcare beyond regular hours), allowing flexible shifts or providing additional staff support, including additional security during late hours.

However, it is not just women who need flexibility or other support services in the workplace. Today, in many industries, men are automatically assigned to the later shifts and expected to work longer hours. Flexible and fair policies will enable all employees to be more productive without creating further discrimination or stereotyping against one specific group.

As such, employers need to start thinking long term, looking for innovative solutions to provide flexible support systems that are not only beneficial for women, but for all employees within the organisation. The benefits of such measures may not be easy to quantify just yet, but there are already several employers who are doing this because it makes business (and social) sense to them.

The good news: some employers are already showing the way

The IT/BPO sector was one of the first in the country which realised the value of tapping into the female workforce. A recent NASSCOM press release states that more than half the IT/BPO firms will have up to 60 percent women in senior levels and 20 percent in the C-Suite soon. They further stated that “HR policies such as conveyance, flexi-work, work-from-home, parental leave, anti-harassment, (and) healthcare have led to the positive trend”. This development comes on the back of continued growth and profitability of the technology and BPO industry.

While it may be easier to have flexible policies around work in the IT industry, even industries that don’t generally take to flexibility are doing their bit to make it easier for women (and men) to work. Take the case of Tata’s Starbucks, one of the employers we worked with as part of our retail programme that has an organisational mandate on gender diversity.

Starbucks has invested in a number of effective interventions for women. These include interactions with family and friends at the workplace, flexible working hours for young mothers, and structured career paths for part-timers. Women are not penalised for part-time work when it comes to promotions and there are a number of successful cases of part-timers becoming shift managers and store managers.

Within a year of investing in these interventions, Starbucks has seen a significant jump in the number of women on the rolls, helping improve staff retention rates. While it is still a work in progress, there is early and clear evidence to show that stores with higher gender diversity have higher footfalls and revenue as well.

Take another example. Angel Stores are Vodafone retail outlets managed and run entirely by women employees, including security, pantry staff, customer service resources, as well as management level personnel. In terms of the scale of operations, average footfalls or ratio of male and female customers, Angel Stores operates in the same way as any other Vodafone retail outlet. They cater to the product and service needs of all customers and are undifferentiated in all aspects, except that the staff members are all women.

Customers of Vodafone's Angel Stores say the female staff are friendly and patient, allowing them to enjoy an enhanced overall shopping experience. With 34 Angel Stores across 21 circles in the country, Vodafone’s aspiration is to be the world’s best employer for women.

As more employers define the new norms of a workplace, especially given the changing nature of work itself, the business case for gender diversity should finally find wider acceptance.

What would it take to create an equitable workforce?

The first step towards building an equitable workforce is building awareness about job roles and opportunities amongst women and their families. This cannot be done without taking into consideration existing cultural practices. However, our experience shows that economics usually trumps culture. Once families realise that the woman of the house can be an active contributor, support typically increases.

But that first step of sensitising parents, spouses, siblings, and the woman herself about the potential of women outside of the boundaries of the house is critical. This point has been well articulated by Rohini Pande, who says policy responses could prove critical when the problem is rooted in social and behavioural norms, rather than a lack of resources.

An interesting recommendation, supported with evidence from the micro-credit sector, is the need to foster women’s social networks. Women are more likely to complete courses, take loans for business purposes and report higher household income and consumption when they bring a friend along. Investing in scalable behavioural change initiatives to break prevailing gender stereotypes at a national scale will call for some bold philanthropy.

Secondly, partnering with forward-thinking employers to demonstrate scalable solutions is equally crucial, something Sattva has been actively working on. As seen earlier, customer experience is one field where there is already a strong business case for employing more women. By working with progressive employers in high-growth industries and implementing specific interventions targeted at increasing the number of women, a wider case for employment of women can be established. This would require investment in ecosystem building activities such as research and measurement systems to build the evidence at an organisational level, not just at a macroeconomic one.

Thirdly, investing in women’s employability to enter or re-enter the workforce and providing flexible opportunities for women acquire the necessary job-related skills, while keeping the various demands on their time in mind is critical. In a world where blended learning is fast becoming the norm, women are naturally placed to make the most of this trend. As part of our work, we hope to bring about further innovation in making low-cost, flexible training programmes available for women.

Finally, the wide gap in Indian women’s participation in the workforce only means that there will be a cost associated with bridging this gap. While this cost would ultimately need to be borne by the employers and the women (and their families) themselves, in the short term, this would require significant support from the government as well as philanthropic organisations -- both for advocating and creating policy and systems, as well as for implementing them.

Having said that, we truly believe that these are not “costs”, but “investments” in the country’s future.

It is our hope that Preethi* and the many other women like her will no longer have to fight alone nor have to give up on their dreams of being a part of the workforce. It is our hope, too, that they have equal opportunities to live productive and meaningful lives, earning the respect and credit that they are due, both in the workplace and in their communities. Why, you may ask. The answer to this question is simple and aptly summed up in a popular tagline: “Because they’re worth it.”

*All the names of the women cited in this article have been changed; all anecdotes are true.

Anita Kumar is Head, Solutions at Sattva, an organisation aimed at delivering high social impact on the ground by working in partnership with multiple stakeholders. The learnings in this piece have specifically been informed by Sattva’s work with JP Morgan Philanthropy Initiatives, FOSSIL Foundation, TRRAIN, SPI-Rockefeller Foundation, UNDP, Labournet, LEAP Skills, Unnati and AVTAR I-WIN. To know more about the “Women in Workforce” solution or to reach the author, please write to [email protected].