Netflix film 'Sir' is a delicate tale of love and blurring class divisions in the time of moral policing

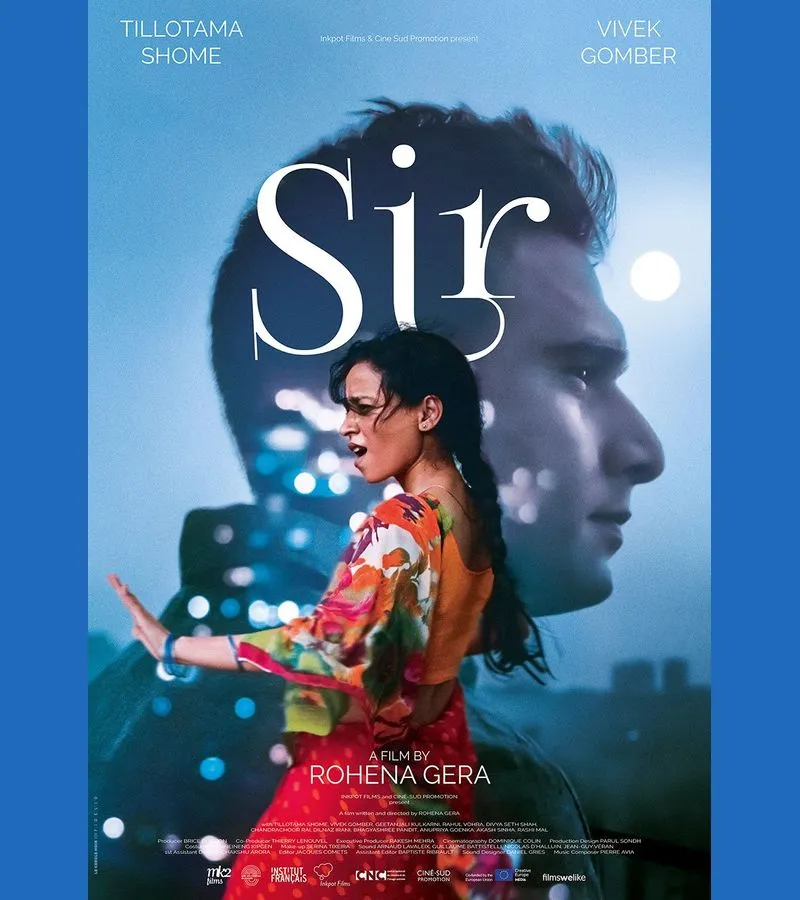

In this week’s edition of YourStory Reviews, we look at Rohena Gera’s 'Sir' starring Tillotama Shome and Vivek Gomber. The widely appreciated film is currently streaming on Netflix.

“There is a charm about the forbidden that makes it unspeakably desirable.” — Mark Twain.

Simply put, Sir is a story of forbidden love. But it’d be a disservice to call it just that. The film’s title is prefixed with ‘Is Love Enough?’ and that is the question it seeks to answer in its 98 minutes of run-time.

Originally premiered at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, Sir opened in India in November 2020, and released on Netflix a month later. Since then, it has featured among the top three most-watched titles on the streaming platform.

A delicate, slow-burning romance between a wealthy NRI writer Ashwin (a sublime Vivek Gomber, last seen in A Suitable Boy) and his housemaid Ratna (Tillotama Shome, in possibly her career-best performance), Sir explores the social, economic, and emotional contours of an unequal match in the bustling metropolis of Mumbai.

Tillotama Shome and Vivek Gomber play the leads in Sir

The film opens with its protagonists returning home. He’s called off his wedding after being cheated on by his fiancée, and she’s been summoned back to ‘work’ from her village as a result of the developments in her employer’s (sir) life.

As a dejected Ashwin spends his days locked up in his swanky apartment in a South Bombay high-rise, the caring and attentive Ratna cooks, cleans, fields phone calls on his behalf, and just lets him be.

Gradually, their silence and loneliness start getting punctuated with awkward exchanges that, in turn, give the viewers a deeper insight into their lives and personalities.

“Life kabhi khatam nahi hota, Sir [Life goes on, Sir],” she tells the man who’s nursing a broken heart.

Sir is currently one of the top 3 titles on Netflix India

Director Rohena Gera underscores the differences between Ashwin and Ratna from the outset — he’s sophisticated and privileged, she’s a village lass; he has vast empty rooms and corridors to himself, she’s cramped up in a tiny servants quarter; he watches avant-garde French films for leisure, she lip-syncs to local songs on TV; he uses English with people of his social class, breaking into Hindi only while instructing the help; she speaks Marathi with a rustic twang, switching to Hindi to establish a common ground with the employer; he’s shunned his family business to pursue a career abroad, she’s suppressed her dreams to save up for her sister’s education.

And yet, the glaring disparities notwithstanding, one can’t help but notice the little things that tie Ashwin and Ratna together, making their romance more real and felt.

They are sensitive, dignified, and polite to a fault. She was widowed at 19, he’s just lost a partner. Both have buried something — he, a “half-written” novel and she, a “fashion designer” course — underneath family compulsions and responsibilities.

The lovers are acutely aware of what they’re up against, often concealing more than revealing their real desires. Nonetheless, in the deafening emptiness of Mumbai, class divisions blur as Ashwin and Ratna get drawn to each other — gradually, and then all at once.

Shome is outstanding as Ratna, almost internalising the character and its pleasures and pains. Gomber is subtle, effortless, and a perfect ally to her brilliance.

Sir poster for release in Europe

Director Gera uses spaces and silences smartly. As they get closer, Ashwin and Ratna start inhabiting the same frames — living room, dining table, elevator, and terrace. Their romance is beautifully understated, and more is expressed when less is said.

Sir also serves as a sharp critique of the privileged upper class that often dehumanises domestic workers. It lends voice and direction to Ratna’s dreams and desires.

Parts of the film are a throwback to the Monica Dogra-Prateik Babbar track from Kiran Rao’s acclaimed arthouse film Dhobi Ghat. The class-defying bond between an NRI filmmaker and a dhobi (washerman), the unkind judgements of friends and family, the hard-hitting realities that threaten to tear apart an almost Utopian bond, and Maximum City bearing witness to it all — these themes find their way to Sir too.

Both films, helmed by women directors, are nuanced and affecting portrayals of forbidden love that will compel you to take a hard look at your own class biases.

Historically, in cinema and literature, romantic love has often challenged long-established societal structures, invaded territories, broken down literal walls, won battles, and much more.

But in 21st century India, when moral policing is at its shrillest, can a young man and his widowed ‘servant’ find love? Your guess is as good as ours.

Edited by Saheli Sen Gupta